‘Men on Boats’ is like a Frederick Remington painting come to life

Just three performances of Theatre Conspiracy’s production of Men on Boats remain. If you’re not familiar with the plotline, the play recounts the federally-sponsored 1869 expedition by John Wesley Powell and a ragtag assemblage of former soldiers, misfits and ne’er-do-wells to explore and map the Green

Just three performances of Theatre Conspiracy’s production of Men on Boats remain. If you’re not familiar with the plotline, the play recounts the federally-sponsored 1869 expedition by John Wesley Powell and a ragtag assemblage of former soldiers, misfits and ne’er-do-wells to explore and map the Green  and Colorado Rivers and, ultimately, the Grand Canyon. The twist in playwright Jacklyn Backhaus’ mostly true retelling of the story of these ten white cisgender adventurers is that the cast is entirely female, and so is the show’s director (Rachael Endrizzi), stage manager (June Koc) and costumer (Diana Waldier).

and Colorado Rivers and, ultimately, the Grand Canyon. The twist in playwright Jacklyn Backhaus’ mostly true retelling of the story of these ten white cisgender adventurers is that the cast is entirely female, and so is the show’s director (Rachael Endrizzi), stage manager (June Koc) and costumer (Diana Waldier).

While the play takes the man out of “manifest destiny” and satirizes the testosterone-fueled bravado of Wild West explorers on a mission to discover places they can name after themselves, Men on Boats is at its essence about leadership, trust, the bonds forged (and broken) when a group finds itself under constant threat of injury, starvation and death,

While the play takes the man out of “manifest destiny” and satirizes the testosterone-fueled bravado of Wild West explorers on a mission to discover places they can name after themselves, Men on Boats is at its essence about leadership, trust, the bonds forged (and broken) when a group finds itself under constant threat of injury, starvation and death,  and the dynamics of risk-taking.

and the dynamics of risk-taking.

Each of the members of Rachael Endrizzi’s cast does an exemplary job of excavating these themes from the action and dialogue that Backhaus painstakingly wove into the fabric of her script, but it is the interplay  between one-armed John Wesley Powell and able-bodied William Dunn that most aptly explores the latter risk-reward dichotomy. Played to perfection respectively by Shelley Sanders and Anna Grilli, Powell and Dunn are flip sides of the risk-taking coin. Powell is the eternal optimist, anticipating triumph, reward and vindication

between one-armed John Wesley Powell and able-bodied William Dunn that most aptly explores the latter risk-reward dichotomy. Played to perfection respectively by Shelley Sanders and Anna Grilli, Powell and Dunn are flip sides of the risk-taking coin. Powell is the eternal optimist, anticipating triumph, reward and vindication  around every bend in the river. Although not entirely risk averse, Dunn clearly has a risk tolerance limit that makes it difficult for her to deal with the uncertainty that is implicit in any exploration, particularly one as risky as venturing into rugged terrain in the heart of Indian territory.

around every bend in the river. Although not entirely risk averse, Dunn clearly has a risk tolerance limit that makes it difficult for her to deal with the uncertainty that is implicit in any exploration, particularly one as risky as venturing into rugged terrain in the heart of Indian territory.

As the expedition progresses, Dunn’s increasing uneasiness becomes palpable. It causes her to question Powell’s judgment and  challenge her every decision. But more than fear of death or physical harm lies at the heart of Dunn’s growing disenchantment with the expedition and disillusionment with her friend. First, there is Dunn’s fear of the unknown, of having no idea of the perils that await the intrepid explorers downstream. There’s also Dunn’s fear of failing, of the embarrassment and

challenge her every decision. But more than fear of death or physical harm lies at the heart of Dunn’s growing disenchantment with the expedition and disillusionment with her friend. First, there is Dunn’s fear of the unknown, of having no idea of the perils that await the intrepid explorers downstream. There’s also Dunn’s fear of failing, of the embarrassment and  public humiliation that the mission’s failure will inevitably entail.

public humiliation that the mission’s failure will inevitably entail.

All of us in “the cheap seats” can identify to varying degrees with fears such as these. We might be tempted to attribute our aversion to doing something as inherently dangerous as exploring an uncharted wilderness or white water rafting (or taking a Blue  Origin or SpaceX vehicle into outer space) as a lack of courage. But what differentiates Powell and Dunn is not a surfeit or lack of courage, but rather self-confidence. In spite of having only one arm and thereby being physically unable to perform the tasks and duties she demands from the rest of the party, John Wesley Powell is supremely confident in her intelligence, ingenuity and ability to

Origin or SpaceX vehicle into outer space) as a lack of courage. But what differentiates Powell and Dunn is not a surfeit or lack of courage, but rather self-confidence. In spite of having only one arm and thereby being physically unable to perform the tasks and duties she demands from the rest of the party, John Wesley Powell is supremely confident in her intelligence, ingenuity and ability to  prevail.

prevail.

But here’s the rub. Self-confidence is not an inherited trait. We are not born with or without it. It’s a learned skill that is developed and honed by the failures we experience and overcome. All that’s required is the pluck to confront our fears and the resolve to learn from our mistakes. John Wesley Powell’s friend, Ulysses S. Grant, is a classic  illustration of this principle. Prior to becoming the Civil War’s iconic general and the country’s 18th president, Grant had failed as a soldier, a farmer and a real estate agent. In fact, when the Civil War started, he was working as a lowly handyman for his father.

illustration of this principle. Prior to becoming the Civil War’s iconic general and the country’s 18th president, Grant had failed as a soldier, a farmer and a real estate agent. In fact, when the Civil War started, he was working as a lowly handyman for his father.

In portraying Powell, Sanders not only demonstrates this aspirational quality, but the compassion Powell  feels for those who, like Dunn, sabotage their hopes, dreams and aspirations through self-doubt and reluctance to step outside their personal comfort zone.

feels for those who, like Dunn, sabotage their hopes, dreams and aspirations through self-doubt and reluctance to step outside their personal comfort zone.

But while meaty themes like risk-taking, risk aversion and the role that self-confidence plays in both cannot – and should not – be gainsaid, there’s more afoot in Men on Boats.

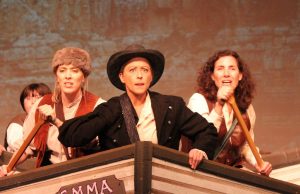

Compliments of Endrizzi, the acting is crisp. (Shout-outs to Tiffany Campbell, Shaun Cott, Carmen Crussard, Holly Zammerilla, Kay O’Connell, Anne Reed, Stacey Stouffer and Kendra Weaver.) The props – from the riverboats (which consist of the Emma Dean, Kitty Clyde’s Sister, Maid of the Canyon and No Name) to the campfires and oaken barrels of Schlitz Beer – evoke an old-time, frontier feel that is ably matched by the

Compliments of Endrizzi, the acting is crisp. (Shout-outs to Tiffany Campbell, Shaun Cott, Carmen Crussard, Holly Zammerilla, Kay O’Connell, Anne Reed, Stacey Stouffer and Kendra Weaver.) The props – from the riverboats (which consist of the Emma Dean, Kitty Clyde’s Sister, Maid of the Canyon and No Name) to the campfires and oaken barrels of Schlitz Beer – evoke an old-time, frontier feel that is ably matched by the  outfits conjured by Diana Waldier and the music playing before and during the show. And the scenery – which comes in the form of projected panoramas – is absolutely breathtaking. Against that soaring backdrop, the action unfolding on the Foulds Theatre stage is like a Charles Marion Russell, Albert Bierstadt or Frederick Remington painting come to life.

outfits conjured by Diana Waldier and the music playing before and during the show. And the scenery – which comes in the form of projected panoramas – is absolutely breathtaking. Against that soaring backdrop, the action unfolding on the Foulds Theatre stage is like a Charles Marion Russell, Albert Bierstadt or Frederick Remington painting come to life.

If  you’ve ever embarked upon a multi-day canoe trip that required several hours of portage, if you’ve ever dared yourself to white water raft on the Green, Salmon or Colorado River, if you’ve ever gone camping where dinner depended in whole or in part on what you could catch or hunt, then you’ll also find Men on Boats somewhat nostalgic. The river and camping scenes are that realistic. And if

you’ve ever embarked upon a multi-day canoe trip that required several hours of portage, if you’ve ever dared yourself to white water raft on the Green, Salmon or Colorado River, if you’ve ever gone camping where dinner depended in whole or in part on what you could catch or hunt, then you’ll also find Men on Boats somewhat nostalgic. The river and camping scenes are that realistic. And if  you haven’t had the pleasure, then you’re in for a vicarious treat. After a year-and-a-half of varying degrees of quarantine and travel restrictions, don’t we all jones for a little adventure?

you haven’t had the pleasure, then you’re in for a vicarious treat. After a year-and-a-half of varying degrees of quarantine and travel restrictions, don’t we all jones for a little adventure?

But time’s short. Remaining performances are tonight and Saturday nights at 7:30 and Sunday’s closing 2:00 p.m. matinee.

October  29, 2021.

29, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.