‘Chechens’ message worth pondering in age of increasing division

On stage in the Foulds Theatre at the Alliance for the Arts for six more shows is Phillip Christian Smith’s The Chechens. Winner of the 2019 Theatre Conspiracy New Play Contest, the play features three strong female characters who share a close and caring relationship with each other and their youngest son/younger brother who wants only to be free to be who he is and love who he wants. That, unfortunately,

On stage in the Foulds Theatre at the Alliance for the Arts for six more shows is Phillip Christian Smith’s The Chechens. Winner of the 2019 Theatre Conspiracy New Play Contest, the play features three strong female characters who share a close and caring relationship with each other and their youngest son/younger brother who wants only to be free to be who he is and love who he wants. That, unfortunately,  is impossible in the repressive culture in which he has grown up, where “blue boys” are being rounded up and detained in a camp on the outskirts of town.

is impossible in the repressive culture in which he has grown up, where “blue boys” are being rounded up and detained in a camp on the outskirts of town.

There’s much to unpack when it comes to discussing The Chechens.

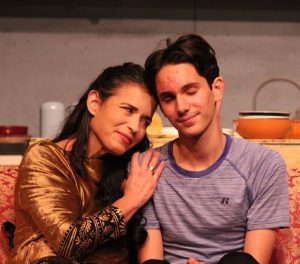

To begin with, this is an extremely well-acted play.  Since making her Southwest Florida theater debut in 2018 in Ghostbird Theatre Company’s site-specific play Everyone on this Train (performed at the historic Atlantic Coast Line railway station, now the Collaboratory), Sharon Isern has performed in nearly a dozen other productions including, most recently, as bride-to-be Courtney in One Slight Hitch for The Studio Players. This, by far, is her best performance to date. Thanks to Phillip Christian Smith, the character of Dagmara provides Isern

Since making her Southwest Florida theater debut in 2018 in Ghostbird Theatre Company’s site-specific play Everyone on this Train (performed at the historic Atlantic Coast Line railway station, now the Collaboratory), Sharon Isern has performed in nearly a dozen other productions including, most recently, as bride-to-be Courtney in One Slight Hitch for The Studio Players. This, by far, is her best performance to date. Thanks to Phillip Christian Smith, the character of Dagmara provides Isern  with the opportunity to explore and convincingly portray a range of attitudes and emotions. Her scenes toward the end of this play will astonish and astound.

with the opportunity to explore and convincingly portray a range of attitudes and emotions. Her scenes toward the end of this play will astonish and astound.

Hollis Galman is wonderful as the widowed matriarch of a family of free thinkers in a strongly patriarchal society and culture. As the story unfolds, it seems that mamma’ s biggest problem is fending off the unwelcome advances of her deceased husband’s overbearing brother, Usman, who feels entitled to replace his brother as the object of Raisa’s affections. Although she has raised two independent, refreshingly opinioned daughters, Raisa is no pushover. She knows what she wants and is fully capable of looking after herself and her interests. Hollis Galman is also fairly new to the Southwest Florida theater scene, although not necessarily to theater, having appeared in a number of Off-Broadway productions during her

entitled to replace his brother as the object of Raisa’s affections. Although she has raised two independent, refreshingly opinioned daughters, Raisa is no pushover. She knows what she wants and is fully capable of looking after herself and her interests. Hollis Galman is also fairly new to the Southwest Florida theater scene, although not necessarily to theater, having appeared in a number of Off-Broadway productions during her  20-year tenure as a New York City public school teacher. Like Isern, she is establishing an enviable reputation as a terrific character actor, as anyone who saw her as Ethel Thayer in On Golden Pond or Marty in Circle Mirror Transformation will eagerly attest.

20-year tenure as a New York City public school teacher. Like Isern, she is establishing an enviable reputation as a terrific character actor, as anyone who saw her as Ethel Thayer in On Golden Pond or Marty in Circle Mirror Transformation will eagerly attest.

Madelaine Weymouth turns in yet another inspired  performance, this time as a sharp-tongued, rebellious younger daughter/sister, Elina, who doesn’t just criticize the machinations of repressive Chechen governmental policies that dehumanize, target and remove so-called degenerates from society in the same way that the Nazis did in the 1930s, but calls “BS” to anyone who supports such policies, including her detested and detestable uncle. As a theater instructor, director and actor, Weymouth fully understands the importance of being present in every scene, and true to form,

performance, this time as a sharp-tongued, rebellious younger daughter/sister, Elina, who doesn’t just criticize the machinations of repressive Chechen governmental policies that dehumanize, target and remove so-called degenerates from society in the same way that the Nazis did in the 1930s, but calls “BS” to anyone who supports such policies, including her detested and detestable uncle. As a theater instructor, director and actor, Weymouth fully understands the importance of being present in every scene, and true to form,  her presence in Chechens lends an aura of authenticity not only to her character, but to the entire family dynamic at play in this drama.

her presence in Chechens lends an aura of authenticity not only to her character, but to the entire family dynamic at play in this drama.

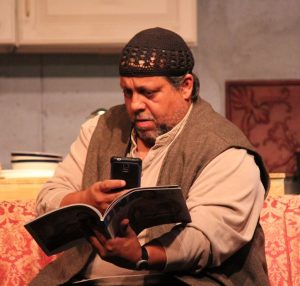

It is often said that a strong villain is an essential ingredient of a strong plotline and larger-than-life characters. That is certainly true of Chechens. But what makes Uncle Daddy (or is it Daddy Uncle) so malevolent is that Phillip Christian Smith’s antagonist is both  decent and compassionate in many respects. While he may wish to take his brother’s place in the mind and heart of his widow, Usman does not force himself upon Raisa. He also evinces a clear and unmistakable sentimentality when it comes to the idea of family. But that sentimentality has inflexible limits that are defined and governed by his religious beliefs. And that renders him something of an

decent and compassionate in many respects. While he may wish to take his brother’s place in the mind and heart of his widow, Usman does not force himself upon Raisa. He also evinces a clear and unmistakable sentimentality when it comes to the idea of family. But that sentimentality has inflexible limits that are defined and governed by his religious beliefs. And that renders him something of an  Eastern European Greek tragic figure. His fatal flaw is being caught up intractably by a religiosity that threatens to destroy the very thing he wants most in life – to assume his place as the head of his brother’s family. Miguel Cintron is brilliant in the role. It’s been a few years since he appeared as the Almighty in An Act of God for Lab Theater. Cintron picked up where he left off in that show, infusing his Chechens character with an irritatingly omniscient and officious bearing that will make the hair on the back of your neck stand on

Eastern European Greek tragic figure. His fatal flaw is being caught up intractably by a religiosity that threatens to destroy the very thing he wants most in life – to assume his place as the head of his brother’s family. Miguel Cintron is brilliant in the role. It’s been a few years since he appeared as the Almighty in An Act of God for Lab Theater. Cintron picked up where he left off in that show, infusing his Chechens character with an irritatingly omniscient and officious bearing that will make the hair on the back of your neck stand on  edge.

edge.

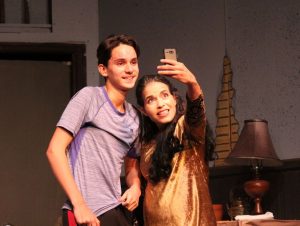

Reuben Garcia is Valid, the son/baby brother in this story. Garcia does a really fine job of portraying a young man coming to terms with both his sexuality and sexual orientation in a household of women and a society that is hostile to the concept of same sex love. It’s hard enough being an adolescent coming to terms with hormones and sexual urges that keep you up late at night, but when you’re gay in a repressive culture, letting others in on the secret can result not just in being ostracized by your own family, but turned over to the authorities as a sexual deviant. And therein lies the crux of what makes the character of Valid so compelling and Garcia’s portrayal so remarkable. He captures and conveys the isolation and desperation under which Valid labors as he contemplates not only losing the love of his devoted mother and doting sisters, but his freedom and his very life.

as a sexual deviant. And therein lies the crux of what makes the character of Valid so compelling and Garcia’s portrayal so remarkable. He captures and conveys the isolation and desperation under which Valid labors as he contemplates not only losing the love of his devoted mother and doting sisters, but his freedom and his very life.

While there is certainly  a surfeit of tumult and drama woven into the fabric of the characters and their interactions, Phillip Christian Smith is to be commended for the smattering of jokes, sibling teasing and gallows’ humor he injects in his masterful dialogue to lighten all the tension. He’s also done a phenomenal job of creating a family dynamic that goes beyond believable. This is a family in which

a surfeit of tumult and drama woven into the fabric of the characters and their interactions, Phillip Christian Smith is to be commended for the smattering of jokes, sibling teasing and gallows’ humor he injects in his masterful dialogue to lighten all the tension. He’s also done a phenomenal job of creating a family dynamic that goes beyond believable. This is a family in which  you’d love to be a member.

you’d love to be a member.

If it takes a village to raise a child, then the message to be gleaned from The Chechens is that we all bear responsibility for creating a climate in which each of us is free to be who we are and love who we want. Or stated conversely, it is incumbent upon us individually and collectively to reject and overthrow those who attack others on the basis of race, religion, ethnicity or gender. Beyond the context and confines of the play’s setting, it is message worth pondering in a  day and age of increasing division, where various segments of the population – whether African-American, Muslim, Latino immigrant or Jew – are marginalized and scapegoated by those seeking to protect, preserve and consolidate their political and economic power.

day and age of increasing division, where various segments of the population – whether African-American, Muslim, Latino immigrant or Jew – are marginalized and scapegoated by those seeking to protect, preserve and consolidate their political and economic power.

It warrants mentioning that The Chechens does possess an element of historical accuracy. In 2015, one hundred gay men  were, in fact, rounded up and held in a camp on the outskirts of town. Three were killed. Some of the others were beaten and tortured in the course of the government-sponsored gay purge. But even after they were released, these men had something else to fear – honor killings at the hands of their own families. Being gay in predominantly Muslim Chechnya is seen as a stain on the family’s honor. Even the extended family is regarded as tainted,

were, in fact, rounded up and held in a camp on the outskirts of town. Three were killed. Some of the others were beaten and tortured in the course of the government-sponsored gay purge. But even after they were released, these men had something else to fear – honor killings at the hands of their own families. Being gay in predominantly Muslim Chechnya is seen as a stain on the family’s honor. Even the extended family is regarded as tainted,  which can make it hard for cousins, nieces and nephews to find suitable partners and marry. So honor killing that looks like suicide is seen by some as the only viable alternative to public shame and indignity.

which can make it hard for cousins, nieces and nephews to find suitable partners and marry. So honor killing that looks like suicide is seen by some as the only viable alternative to public shame and indignity.

Incidents like these may put Chechnya as a country and Muslims as a culture in a poor light. But Chechnya, of course,  is not the only country that criminalizes members of the LBGTQ community. Worldwide, 71 countries have laws that make homosexuality illegal to some extent and degree. Many are in Africa and the Middle East, but it wasn’t that long ago that many states in this country had laws on their books that criminalized gay sex or permitted employers to fire employees or

is not the only country that criminalizes members of the LBGTQ community. Worldwide, 71 countries have laws that make homosexuality illegal to some extent and degree. Many are in Africa and the Middle East, but it wasn’t that long ago that many states in this country had laws on their books that criminalized gay sex or permitted employers to fire employees or  refuse to serve customers on the basis of sexual orientation or identity. And it isn’t just the Quran that contains language which forbids homosexuality. The Christian Bible (in Leviticus for example) contains passages that characterize a man who lies with a man as if a woman as an abomination.

refuse to serve customers on the basis of sexual orientation or identity. And it isn’t just the Quran that contains language which forbids homosexuality. The Christian Bible (in Leviticus for example) contains passages that characterize a man who lies with a man as if a woman as an abomination.

Nevertheless, The Chechens has come under criticism for reinforcing Muslim stereotypes and inducing viewers to categorize  Islam as a non-progressive, extremist religion because of its provincial stance on gay rights. The accusation is one of “pinkwashing,” a term used to connote the advancement of LGBTQ rights at on the backs of marginalized populations like the Muslim community. From this vantage, pro-LGBTQ support is co-opted in the effort to justify and rationalize racist and xenophobic perspectives.

Islam as a non-progressive, extremist religion because of its provincial stance on gay rights. The accusation is one of “pinkwashing,” a term used to connote the advancement of LGBTQ rights at on the backs of marginalized populations like the Muslim community. From this vantage, pro-LGBTQ support is co-opted in the effort to justify and rationalize racist and xenophobic perspectives.

Audience members are free to decide if these objections are valid in any or every way. That might prove to be a topic for robust post-production conversation, which is, after all, the goal of all good theater. With its season devoted to female playwrights (Jordan Hall (Kayak), Jessica Dickey (The Amish Project), Anne Washburn (Mr. Burns, a post-electric play), Jennifer Haley (The Nether), Lillian Hellman (Toys in the Attic) and legacy of plays

Audience members are free to decide if these objections are valid in any or every way. That might prove to be a topic for robust post-production conversation, which is, after all, the goal of all good theater. With its season devoted to female playwrights (Jordan Hall (Kayak), Jessica Dickey (The Amish Project), Anne Washburn (Mr. Burns, a post-electric play), Jennifer Haley (The Nether), Lillian Hellman (Toys in the Attic) and legacy of plays  featuring poignant stories about the black experience in white society (Lydia Diamond (The Bluest Eye), Ntozake Shange (For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf), August Wilson (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Seven Guitars, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, King Hedley II), Lorraine Hansberry (A Raisin in the Sun), Katori Hall (Mountaintop), Theatre Conspiracy has a long tradition of fostering community talkbacks and post-show discussion. However, care should be taken when pursuing this discussion to keep the play’s twofold gravamen firmly in mind,

featuring poignant stories about the black experience in white society (Lydia Diamond (The Bluest Eye), Ntozake Shange (For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf), August Wilson (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Seven Guitars, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, King Hedley II), Lorraine Hansberry (A Raisin in the Sun), Katori Hall (Mountaintop), Theatre Conspiracy has a long tradition of fostering community talkbacks and post-show discussion. However, care should be taken when pursuing this discussion to keep the play’s twofold gravamen firmly in mind,  namely that (1) love is stronger than religious or nationalistic fervor and (2) we have individually and collectively the right and power to reject those who seek to divide us and the responsibility to create a climate that respects every individual and allows us all to be who we are and be with those we love regardless of their race, creed or sexual identity or orientation.

namely that (1) love is stronger than religious or nationalistic fervor and (2) we have individually and collectively the right and power to reject those who seek to divide us and the responsibility to create a climate that respects every individual and allows us all to be who we are and be with those we love regardless of their race, creed or sexual identity or orientation.

August 7, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.