For Lemec Bernard, acting is a blood sport

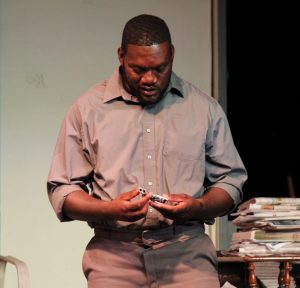

It was a boring Saturday, and Lemec Bernard was looking for something to do. An ad caught his eye. It was for a free acting class; the teacher, Marcus Colón. On a lark, Bernard attended. He had no idea what to expect. Nothing in his background predisposed him toward acting. In college and high school, he was the inveterate jock. Both as a letterman running back and full-ride scholarship outside linebacker at UCF, he was more accustomed to lowering his head, hitting hard, exacting pain. And so when Colón opened the class with the words

It was a boring Saturday, and Lemec Bernard was looking for something to do. An ad caught his eye. It was for a free acting class; the teacher, Marcus Colón. On a lark, Bernard attended. He had no idea what to expect. Nothing in his background predisposed him toward acting. In college and high school, he was the inveterate jock. Both as a letterman running back and full-ride scholarship outside linebacker at UCF, he was more accustomed to lowering his head, hitting hard, exacting pain. And so when Colón opened the class with the words  “Acting is a blood sport,” Bernard was all in.

“Acting is a blood sport,” Bernard was all in.

“It didn’t make sense at first. It took me forever to really understand what he meant, but I do now,” Lemec reflects. “Now, I can’t think of acting in any other way.”

Bernard couches his explanation in competitive terms.

“We’re all vying for something on stage. Either the person  has what you want or they’re in your way. And so because that was my first imprint about what acting is, that’s how I’ve gone about learning the craft.”

has what you want or they’re in your way. And so because that was my first imprint about what acting is, that’s how I’ve gone about learning the craft.”

The key for Bernard is transporting himself into the life, mindset and psyche of the character rather than portraying someone else.

“You’re never acting like somebody or something,” he amplifies. “You’re being yourself in that situation. So whatever  the character is doing or experiencing, pretend that is you doing or experiencing it, and then go from there. I literally act as if I grew up with whatever trials, tribulations and joys that character might have had. And then I think, ‘How would I internalize that?’ That’s how I approach each character, each role.”

the character is doing or experiencing, pretend that is you doing or experiencing it, and then go from there. I literally act as if I grew up with whatever trials, tribulations and joys that character might have had. And then I think, ‘How would I internalize that?’ That’s how I approach each character, each role.”

Bernard acknowledges his good fortune in having Colón introduce him to the world of acting. In addition to instructor,  Marcus Jorel Colón is an actor, author, hip hop artist, radio show host, songwriter, and photographer. His film credits include Black Widow (2014, Andre Bryant), Tethered (2016, police officer) and Hanging Millstone (2018, prosecutor), as well as the 2013 short film Till Death Do Us Part (voodoo man). His theater credits include Bob: A Life in Five Acts (at Laboratory Theater of Florida), Dead Man’s Cellphone (at Florida SouthWestern State College), Relatively Speaking

Marcus Jorel Colón is an actor, author, hip hop artist, radio show host, songwriter, and photographer. His film credits include Black Widow (2014, Andre Bryant), Tethered (2016, police officer) and Hanging Millstone (2018, prosecutor), as well as the 2013 short film Till Death Do Us Part (voodoo man). His theater credits include Bob: A Life in Five Acts (at Laboratory Theater of Florida), Dead Man’s Cellphone (at Florida SouthWestern State College), Relatively Speaking  (at Theatre Conspiracy), I Love You to Death (Starlight Productions), Vickie & Vinny’s Wedding (Starlight Productions) and It’s Not Worth It (Black Elixir Media). He has also produced and co-directed independent projects such as The Storms At Home and Too Much Drama for the entertainment company he co-owns with his wife LaShanda Hutchins Colón. A published poet, he is a former theatre arts scholarship student at Florida SouthWestern State College

(at Theatre Conspiracy), I Love You to Death (Starlight Productions), Vickie & Vinny’s Wedding (Starlight Productions) and It’s Not Worth It (Black Elixir Media). He has also produced and co-directed independent projects such as The Storms At Home and Too Much Drama for the entertainment company he co-owns with his wife LaShanda Hutchins Colón. A published poet, he is a former theatre arts scholarship student at Florida SouthWestern State College  and has taught acting at Thespian Production in Fort Myers.

and has taught acting at Thespian Production in Fort Myers.

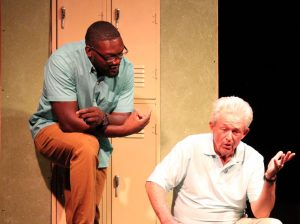

But Lemec’s good fortune did not end there. He also met his muse and work-wife, Cantrella Canady, in that class and in the show that Colon was directing, The Storms at Home gospel stage play.

“We did meet in Marcus’ class,” Cantrella confirms. “Then Marcus plucked a few of us from the class to do this show for him,  and that’s when I really got to know him. I started out as his mother, and then his character’s girlfriend, and every production since then we’ve been opposites except for A Raisin the Sun and King Hedley II.”

and that’s when I really got to know him. I started out as his mother, and then his character’s girlfriend, and every production since then we’ve been opposites except for A Raisin the Sun and King Hedley II.”

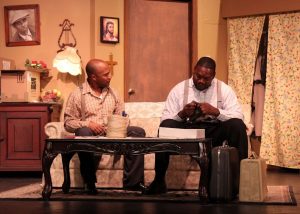

In addition to The Storms at Home, A Raisin in the Sun and King Hedley, Lemec and Cantrella have shared the boards in Mr. Burns: A Post Electric  Play (he was Homer and she was Bart), Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (where they were spouses separated when he was enslaved for seven years by Joe Turner) and Engagement Rules (in which they’re engaged and grappling with the decision over whether to keep or abort the baby she just learned that she’s unexpectedly carrying).

Play (he was Homer and she was Bart), Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (where they were spouses separated when he was enslaved for seven years by Joe Turner) and Engagement Rules (in which they’re engaged and grappling with the decision over whether to keep or abort the baby she just learned that she’s unexpectedly carrying).

“What I like about  acting is the competition, all day, every day and twice on Sunday,” says Lemec, returning to the blood sport theme. “It is a competition between me and whoever’s on stage. If we’re really going to bring our characters to life, then we need feed off each other’s emotions.”

acting is the competition, all day, every day and twice on Sunday,” says Lemec, returning to the blood sport theme. “It is a competition between me and whoever’s on stage. If we’re really going to bring our characters to life, then we need feed off each other’s emotions.”

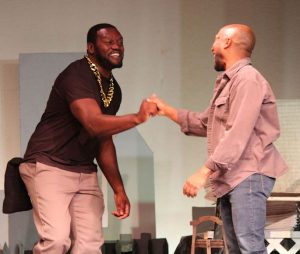

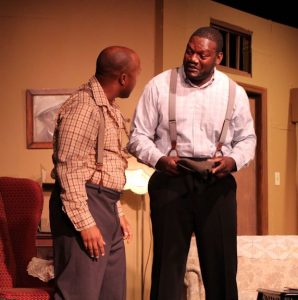

He cites Derek Lively as an example of a competition partner.

“He’ll surprise me by saying his lines in a different way and I have to react appropriately. If he’s getting amped up,  I have to get amped up. If he’s acting quietly, I have to dial it back too. ‘You gotta leave the money in the pot’ [he says at one point in Hedley]. He says it so tenderly that it makes me feel like he’s my friend and so I’m happy to acquiesce to that. But another night, he might couch it as a demand, so I gotta stand up for myself and not give in to that.”

I have to get amped up. If he’s acting quietly, I have to dial it back too. ‘You gotta leave the money in the pot’ [he says at one point in Hedley]. He says it so tenderly that it makes me feel like he’s my friend and so I’m happy to acquiesce to that. But another night, he might couch it as a demand, so I gotta stand up for myself and not give in to that.”

What  Lemec is describing clearly supercedes memorizing lines, blocking and intent. It demands the same quantum and quality of focus and concentration as playing on the gridiron during the final two minutes of a tight game.

Lemec is describing clearly supercedes memorizing lines, blocking and intent. It demands the same quantum and quality of focus and concentration as playing on the gridiron during the final two minutes of a tight game.

“There are nuances every night and I have to be on my toes and alert to that,” he underscores.

Hence the competition.

But the competition Lemec postulates exists exclusively between the characters the actors are portraying. Since the audience hasn’t been present for any other shows or rehearsals, they have no basis for comparison.

But the competition Lemec postulates exists exclusively between the characters the actors are portraying. Since the audience hasn’t been present for any other shows or rehearsals, they have no basis for comparison.

It’s also a matter of professional pride.

“Derek has been acting for years. If he raises the stakes, I better raise the stakes too. I want you to see me on the same level, on the  same plane as he is. I don’t want the audience to walk out of the show saying he’s got all this experience and I’m relatively new. I want them saying, ‘Those two were really dynamic.’ In order for that to happen, I need to do whatever is necessary to bring myself up to that level.”

same plane as he is. I don’t want the audience to walk out of the show saying he’s got all this experience and I’m relatively new. I want them saying, ‘Those two were really dynamic.’ In order for that to happen, I need to do whatever is necessary to bring myself up to that level.”

And that applies regardless of whether the other actor is male or female, whether the emotion that’s called for is aggression or tenderness. In fact, as Tom in Engagement Rules, audiences got to see a much softer, sentimental  side of this talented young actor who has the chops to play both dramatic and comedic roles.

side of this talented young actor who has the chops to play both dramatic and comedic roles.

“No matter what the role is, my character must show up no matter how inconsequential the line or scene may be.”

And that dynamic doesn’t change based on the playwright.

“While they may put the words on a page, it’s the actor who has to bring those words to life.”

The end result is a better show, a more convincing production, and more satisfying product for cast, crew and the audiences who see the performances.

“When I played sports, I played as though every game was my last game ever. Now I perform as if every show is my last appearance on stage. The way a Michael Jordan or Lebron James approaches their sport. Just like they’re going to dunk as hard as they can or shoot every three as best they can, same with performing. You want to leave the audience wondering why he played it that way or why the playwright wrote it that way, not thinking ‘he was okay.’”

“When I played sports, I played as though every game was my last game ever. Now I perform as if every show is my last appearance on stage. The way a Michael Jordan or Lebron James approaches their sport. Just like they’re going to dunk as hard as they can or shoot every three as best they can, same with performing. You want to leave the audience wondering why he played it that way or why the playwright wrote it that way, not thinking ‘he was okay.’”

On average, Bernard does one show each season. If you want to know what he’ll be in next, find out where Cantrella is appearing. So far,  she’s been the common denominator.

she’s been the common denominator.

“She has such a dynamic range,” Lemec points out. “I’m always learning something from her, especially in terms of intent. There’s no wasted movements where Cantrella’s concerned. Everything she does, every step she takes on stage leads her somewhere else. She’s amazing.”

Their admiration is mutual.

Their admiration is mutual.

“He’s very humble, but he’s also a perfectionist,” Cantrella assesses. “He always takes me by surprise at how talented he is. Once his switch is flipped, he’s on like a hundred percent.”

Since Bernard keys his performance to what’s happening on stage, he confesses that there’s a difference between rehearsals and performances – just like there’s an obvious difference between practice and game speed.

between practice and game speed.

“The magical things you might see Tom Brady do in a game, most likely he’d never do in practice because he doesn’t need to go that fast or move that quickly since nobody’s trying to kill him. Now tech week, that’s game speed. So if there’s supposed to be really raw  emotions, you’ll see that in tech week. I turn it up a notch to get a feel for it.”

emotions, you’ll see that in tech week. I turn it up a notch to get a feel for it.”

And he turns up the intensity, the focus, the concentration even more during each live performance.

Lemec expects to continue to do theater for the foreseeable future, although he does cop to being curious about whether his  newfound and developing skill set as a stage actor translates to film.

newfound and developing skill set as a stage actor translates to film.

“But either way, I’m nowhere near where I want to be or what I’d like to be. I’m still working to get better.” And for that to happen, he needs to “go against better actors  than me and rise to that level of competition. “

than me and rise to that level of competition. “

In the final analysis, acting is a blood sport.

“Even when I watch other actors on stage or in film, I can see how that’s true.”

And for Lemec Bernard, everything flows from that starting point.

May 9, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.