Caloosahatchee Manuscripts

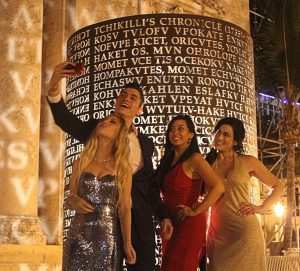

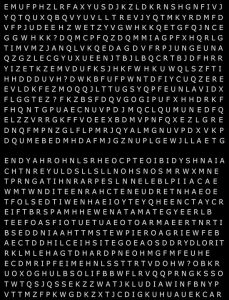

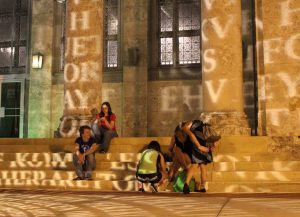

At night, the tapered Ionic columns and limestone steps of the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center glow with the images of thousands of letters like a phosphorous alphabet soup. The source of this bedazzling light show are two large bronze cylinders that sit on the sidewalk at the foot of SBDAC’s stairs. They are a dual point light sculpture called Caloosahatchee Manuscripts, a gift to the

At night, the tapered Ionic columns and limestone steps of the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center glow with the images of thousands of letters like a phosphorous alphabet soup. The source of this bedazzling light show are two large bronze cylinders that sit on the sidewalk at the foot of SBDAC’s stairs. They are a dual point light sculpture called Caloosahatchee Manuscripts, a gift to the  City of Fort Myers made in 2001 by Florida Power & Light Co.

City of Fort Myers made in 2001 by Florida Power & Light Co.

FPL commissioned the work to commemorate the conversion of its power plant on the south bank of the Caloosahatchee River from oil to natural gas. “In 1998, Florida Power & Light decided to re-power its Fort Myers power plant,” Next Era Energy/FPL Media Relations and Senior Spokesman Neil  Nissan recalls. “It was built in the 1950s, and we weren’t using oil any more. So we converted the plant to natural gas, which is much cleaner and served to reduce the oil barge traffic on the river. We wanted to commemorate the occasion and asked the community what we should do.”

Nissan recalls. “It was built in the 1950s, and we weren’t using oil any more. So we converted the plant to natural gas, which is much cleaner and served to reduce the oil barge traffic on the river. We wanted to commemorate the occasion and asked the community what we should do.”

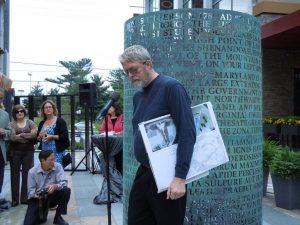

A community advisory board was convened and among the suggestions they made was the donation of an artwork to be placed in front of the old federal courthouse which Jim Griffith and Florida Arts were busily renovating into a visual and performing arts cultural center. A national call to artists was issued and Maryland sculptor Jim Sanborn was ultimately selected.

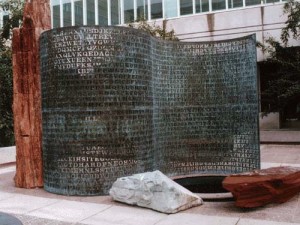

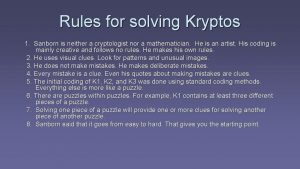

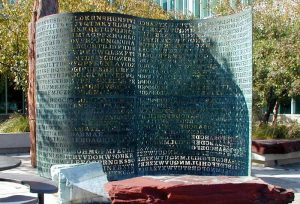

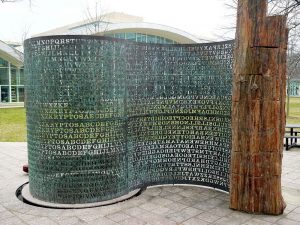

By 2001, Sanborn had built a formidable reputation for heady light sculptures. In 1990, he had been commissioned to do a work for the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia. He delivered a work called Kryptos. Contained within the polished red granite, quartz, copperplate and lodestone were four encrypted messages meant as a challenge to the Agency’s elite code-breakers. In the ensuing decade, the CIA’s cryptologists duly deciphered three of the four messages. But they couldn’t break the

By 2001, Sanborn had built a formidable reputation for heady light sculptures. In 1990, he had been commissioned to do a work for the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia. He delivered a work called Kryptos. Contained within the polished red granite, quartz, copperplate and lodestone were four encrypted messages meant as a challenge to the Agency’s elite code-breakers. In the ensuing decade, the CIA’s cryptologists duly deciphered three of the four messages. But they couldn’t break the  fourth code and that encryption remains unsolved to this day.

fourth code and that encryption remains unsolved to this day.

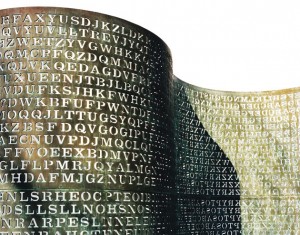

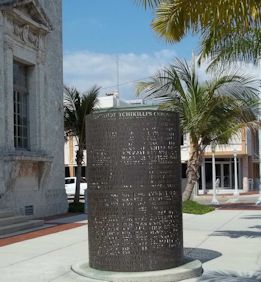

The light sculpture consists of two bronze projection cylinders 8 feet tall by 5 feet in diameter with a pinpoint light source in their center. Using a water jet cutter, Sanborn incised letters into the bronze which are transferred to the façade, steps and sidewalks surrounding  the art center at night. As is is custom, the sculptor visited the site and did extensive research before choosing the text for each drum.

the art center at night. As is is custom, the sculptor visited the site and did extensive research before choosing the text for each drum.

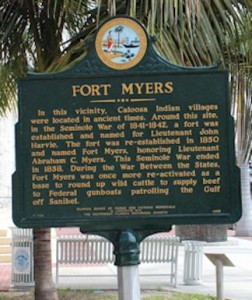

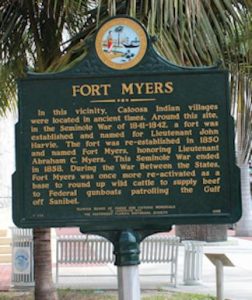

The eastern drum contains the text of a story told by Maskoki Indian leader Tchikilli to James Oglethorpe about the migration of Native Americans into the lower southeast, including Georgia  (where Oglethorpe had founded his colony) and Florida. The Creek, Seminoles and Miccosukee trace their ancestry to Tchikilli and his people, and the Seminoles replaced the Calusa Indians, who lived in this area from 500-1700 A.D. (but became extinct about 200 years after the region was conquered by the Spanish Conquistadors, who arrived in Florida 500 years ago in 1513). When he visited the site for the first time, Sanborn noticed an historical plaque indicating that

(where Oglethorpe had founded his colony) and Florida. The Creek, Seminoles and Miccosukee trace their ancestry to Tchikilli and his people, and the Seminoles replaced the Calusa Indians, who lived in this area from 500-1700 A.D. (but became extinct about 200 years after the region was conquered by the Spanish Conquistadors, who arrived in Florida 500 years ago in 1513). When he visited the site for the first time, Sanborn noticed an historical plaque indicating that  the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center rests on the site of a settlement of Calusa Indians that pre-dates the army fort which eventually gave birth to the city’s name. But “the Calusa Indians left no written record,” Sanborn explains, “so I used the Creek/Seminole legend instead.” Still, he wanted to tie the symbolism of the text to the site, and so called the drum Caloosahatchee Manuscripts, and this is the name by which

the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center rests on the site of a settlement of Calusa Indians that pre-dates the army fort which eventually gave birth to the city’s name. But “the Calusa Indians left no written record,” Sanborn explains, “so I used the Creek/Seminole legend instead.” Still, he wanted to tie the symbolism of the text to the site, and so called the drum Caloosahatchee Manuscripts, and this is the name by which  most people know the work today. [Ed: See below for more on the Maskoki migration legend and Tchikilli, including alternative spellings of these names.]

most people know the work today. [Ed: See below for more on the Maskoki migration legend and Tchikilli, including alternative spellings of these names.]

The western drum is no less historic. As the nearby dedication plaque reveals, “From 1927-1931, Thomas A. Edison studied and tested 13,000-17,000 species of plants for their suitability in the manufacture of a  domestic source of rubber. The plants listed (in Latin) on this cylinder were collected in the Fort Myers area and throughout the State of Florida.” His last grand experiment, Edison undertook the project at the urging of friends Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone, who were hopeful that Edison could find a local source of latex that would lessen their dependence on foreign sources of natural rubber. Latex is produced by many flowering plants, including dandelions

domestic source of rubber. The plants listed (in Latin) on this cylinder were collected in the Fort Myers area and throughout the State of Florida.” His last grand experiment, Edison undertook the project at the urging of friends Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone, who were hopeful that Edison could find a local source of latex that would lessen their dependence on foreign sources of natural rubber. Latex is produced by many flowering plants, including dandelions  (it’s the milky substance that bleeds from the stem when you pick one), gardenias, goldenrod, wisteria and yucca. By 1930, Edison had determined that goldenrod held the most potential for replacing rubber, but by then the 80-year-old Edison was in poor health and he died the following year before finally completing his rubber-replacement experiments.

(it’s the milky substance that bleeds from the stem when you pick one), gardenias, goldenrod, wisteria and yucca. By 1930, Edison had determined that goldenrod held the most potential for replacing rubber, but by then the 80-year-old Edison was in poor health and he died the following year before finally completing his rubber-replacement experiments.

As  fascinating and historically relevant as that may be, what intrigued Sanborn even more was that Edison’s search for a local source of latex was reminiscent of his hunt for a plant material from which to make the filament for his light bulbs. Edison didn’t just invent the light bulb, of course. He combined what he knew about electricity with what he knew about gas lights and invented a whole system of electric lighting. This meant light bulbs, electrical generators, wires to get the electricity from the power station to the homes, fixtures

fascinating and historically relevant as that may be, what intrigued Sanborn even more was that Edison’s search for a local source of latex was reminiscent of his hunt for a plant material from which to make the filament for his light bulbs. Edison didn’t just invent the light bulb, of course. He combined what he knew about electricity with what he knew about gas lights and invented a whole system of electric lighting. This meant light bulbs, electrical generators, wires to get the electricity from the power station to the homes, fixtures  (lamps, sockets, switches) for the light bulbs, and more. It was like a big jigsaw puzzle–and Edison made both the system and its individual pieces.

(lamps, sockets, switches) for the light bulbs, and more. It was like a big jigsaw puzzle–and Edison made both the system and its individual pieces.

The entire effort hinged on finding the right material for the filament–that little wire inside the light bulb. He filled more than 40,000 pages with notes  before he finally had a bulb that withstood a 40-hour test in his laboratory. In 1879, after testing more that 1600 materials for the right filament, including coconut fiber, fishing line, and even hairs from a friend’s beard, Edison and his workers finally figured out what to use for the filament–carbonized bamboo, which is one of the plants that Sanborn incised into the sculpture’s west drum. “Hence the LUX title, and the fact that Florida Power and Light helped fund the project,”

before he finally had a bulb that withstood a 40-hour test in his laboratory. In 1879, after testing more that 1600 materials for the right filament, including coconut fiber, fishing line, and even hairs from a friend’s beard, Edison and his workers finally figured out what to use for the filament–carbonized bamboo, which is one of the plants that Sanborn incised into the sculpture’s west drum. “Hence the LUX title, and the fact that Florida Power and Light helped fund the project,”  Sanborn notes.

Sanborn notes.

Today, the sculpture augments the ambiance of the art center during events, galas and charity balls, and serves as a romantic gathering spot for couples during Art Walk and Music Walk. So whether you call them Caloosahatchee Manuscripts or Lux, Jim Sanborn’s dual point light sculpture illustrates how public art can enhance a space and provide viewers with a unique way in which to learn about the city’s rich historical heritage.

- The physical address of the sculpture is 2301 First Street, Fort Myers, FL 33901

- Its Latitude is N 26° 37′ 13.4381″

- Its Longitude is W 81° 52′ 20.9912″

More About Kryptos

Sanborn has completed more than 125 sculptural installations to date. However, his most famous work remains Kryptos, a $250,000 commission he installed outside the main entrance to the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

Sanborn has completed more than 125 sculptural installations to date. However, his most famous work remains Kryptos, a $250,000 commission he installed outside the main entrance to the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

The sculpture’s name means hidden in Greek and Sanborn duly embedded four puzzles in the curved copper panels that make up the sculpture. He and  a retired CIA cryptographer by the name of Ed Scheidt (a quiet professorial individual fond of hieroglyphic patterns) spent four months devising the type of cryptogram Sanborn would implement. “I could use methods to encrypt [the sculpture] that had an historic basis, that didn’t compromise any current methods [of cryptography used by the government]… I wanted to make something that could eventually be deciphered or

a retired CIA cryptographer by the name of Ed Scheidt (a quiet professorial individual fond of hieroglyphic patterns) spent four months devising the type of cryptogram Sanborn would implement. “I could use methods to encrypt [the sculpture] that had an historic basis, that didn’t compromise any current methods [of cryptography used by the government]… I wanted to make something that could eventually be deciphered or  extracted rather than something that will never be done, ever,” Scheidt comments. He figured that the first parts of the puzzle would take a few years to solve and the last part — maybe ten.

extracted rather than something that will never be done, ever,” Scheidt comments. He figured that the first parts of the puzzle would take a few years to solve and the last part — maybe ten.

“The popular story of Kryptos has long held that CIA analyst David Stein was the first to crack three of the cryptographic sculpture’s four puzzles in 1998,” reports Kim Zetter in a July 10, 2013 post on Wired. “Stein decrypted the coded messages  after spending some 400 hours’ worth of lunch hours working through the puzzles using only paper and pencil. Many people, on and off the CIA campus in Langley, Virginia, had tried to break the coded puzzle, but only Stein, a member of the agency’s Directorate of Intelligence, succeeded. Stein’s work on the code was kept secret, however. In 1999, he wrote a fascinating account of how he cracked three of the sculpture’s four coded messages,

after spending some 400 hours’ worth of lunch hours working through the puzzles using only paper and pencil. Many people, on and off the CIA campus in Langley, Virginia, had tried to break the coded puzzle, but only Stein, a member of the agency’s Directorate of Intelligence, succeeded. Stein’s work on the code was kept secret, however. In 1999, he wrote a fascinating account of how he cracked three of the sculpture’s four coded messages,  but it was only published in an internal CIA newsletter that remained classified until years later. The secrecy over Stein’s achievement allowed California computer scientist Jim Gillogly to steal the spotlight a year later in 1999, when he announced that he’d also cracked the same three messages, only he used a Pentium II to do it.”

but it was only published in an internal CIA newsletter that remained classified until years later. The secrecy over Stein’s achievement allowed California computer scientist Jim Gillogly to steal the spotlight a year later in 1999, when he announced that he’d also cracked the same three messages, only he used a Pentium II to do it.”

But new documents released by the National Security Agency show how that the NSA beat Stein and Gillogly to the punch years earlier. According to records obtained by cracker Elonka Dunin, a game designer who maintains a comprehensive website on Kryptos,  Adm. William O. Studeman, the CIA’s then-deputy director and a former NSA director, issued a formal challenge to his former colleagues at the NSA in 1992 to solve the CIA’s new courtyard puzzle. “The NSA’s director at the time, Vice Admiral Mike McConnell, announced the challenge during an internal ceremony at the NSA, and a

Adm. William O. Studeman, the CIA’s then-deputy director and a former NSA director, issued a formal challenge to his former colleagues at the NSA in 1992 to solve the CIA’s new courtyard puzzle. “The NSA’s director at the time, Vice Admiral Mike McConnell, announced the challenge during an internal ceremony at the NSA, and a  small cadre of cryptanalysts from the agency’s Z Group — the internal name for the cryptanalysts division — ‘enthusiastically responded,’” Zetter relates. “The group was so intent on cracking the code that they formed an informal task force in November 1992, according to the recently released documents, which include a number of internal NSA memos describing how they cracked the ciphers. [T]hey quickly determined, using computer diagnostic tools, that the sculpture consisted of four parts — using at least three different ciphers — and a cryptographic table based on an encryption method developed in the 16th century by a Frenchman named Blaise de Vigenere that was key to helping them solve parts of the puzzle.”

small cadre of cryptanalysts from the agency’s Z Group — the internal name for the cryptanalysts division — ‘enthusiastically responded,’” Zetter relates. “The group was so intent on cracking the code that they formed an informal task force in November 1992, according to the recently released documents, which include a number of internal NSA memos describing how they cracked the ciphers. [T]hey quickly determined, using computer diagnostic tools, that the sculpture consisted of four parts — using at least three different ciphers — and a cryptographic table based on an encryption method developed in the 16th century by a Frenchman named Blaise de Vigenere that was key to helping them solve parts of the puzzle.”

In June 1993, after the three parts were cracked, an internal letter announcing the feat was sent to Admiral McConnell at the NSA, marked “For Official Use Only” and informing him that the deed was done. It was returned with a request to forward the note to Admiral Studeman at the CIA, no doubt with an air of glee and arrogance that the NSA had beat the CIA at cracking its own puzzle.

In June 1993, after the three parts were cracked, an internal letter announcing the feat was sent to Admiral McConnell at the NSA, marked “For Official Use Only” and informing him that the deed was done. It was returned with a request to forward the note to Admiral Studeman at the CIA, no doubt with an air of glee and arrogance that the NSA had beat the CIA at cracking its own puzzle.

The  first encryption was a poetic phrase containing an intentional misspelling that Sanborn composed: “Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion” (“iqlusion” was an intentional misspelling of illusion).

first encryption was a poetic phrase containing an intentional misspelling that Sanborn composed: “Between subtle shading and the absence of light lies the nuance of iqlusion” (“iqlusion” was an intentional misspelling of illusion).

The second puzzle refers to the CIA agent who helped Sanborn with the four puzzles, and the third is a passage from archeologist Howard Carter’s account of  opening the tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922.

opening the tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922.

But the fourth riddle has defied solution.

On Kryptos’ 20th anniversary in November of 2010, Sanborn became so flummoxed by the CIA’s inability to crack the code that he decided to give everyone a clue. Sanborn told The New York Times  that the part of the sculpture that reads “nypvtt” becomes Berlin once decoded. “The ‘Berlin’ clue makes a lot of sense, in historical context of the Berlin Wall coming down that year,” says Elonka Dunin (above). The Berlin Wall came tumbling down in November of 1989, almost exactly a year before the dedication of the Kryptos sculpture at CIA headquarters, and would have been on Sanborn’s mind. Dunin also points out that three slabs of the Berlin Wall sit at CIA headquarters,

that the part of the sculpture that reads “nypvtt” becomes Berlin once decoded. “The ‘Berlin’ clue makes a lot of sense, in historical context of the Berlin Wall coming down that year,” says Elonka Dunin (above). The Berlin Wall came tumbling down in November of 1989, almost exactly a year before the dedication of the Kryptos sculpture at CIA headquarters, and would have been on Sanborn’s mind. Dunin also points out that three slabs of the Berlin Wall sit at CIA headquarters,  a gift from the German government. Although the slabs weren’t dedicated as a monument until 1992 – two years after Kryptos was installed – Dunin thinks it’s possible the CIA had already chosen a spot for them when Sanborn was designing Kryptos and told him about it.

a gift from the German government. Although the slabs weren’t dedicated as a monument until 1992 – two years after Kryptos was installed – Dunin thinks it’s possible the CIA had already chosen a spot for them when Sanborn was designing Kryptos and told him about it.

In conjunction with the new clue release, Sanborn launched a website, Kryptos Clue, to provide an automated  way for people to contact him with their proposed solutions to the puzzle. Over the years, numerous people who were convinced that they’d solved the final puzzle section have contacted him. One woman even showed up at his secluded home on an island. Most of the solutions people have offered have been wildly off-base. Sanborn says that with the launch of

way for people to contact him with their proposed solutions to the puzzle. Over the years, numerous people who were convinced that they’d solved the final puzzle section have contacted him. One woman even showed up at his secluded home on an island. Most of the solutions people have offered have been wildly off-base. Sanborn says that with the launch of his new site, anyone who thinks they’ve solved the last section will have to submit what they believe are the first 10 characters of the final 97 before he will respond.

his new site, anyone who thinks they’ve solved the last section will have to submit what they believe are the first 10 characters of the final 97 before he will respond.

Of course, Sanborn firmly believes that artwork which surrenders its form or content too quickly is soon forgotten. “The Archeological record offers  us a frustratingly fragmented view of the past. Though fragmentary, this archeoview is pregnant with secrets yet to be discovered and is thrilling in its potential. Secrecy is power even if it is just a little something kept from view, buried, so to speak, in the matrix of everyday life,” Sanborn divulges in this context. “For the past 30 years, my task as

us a frustratingly fragmented view of the past. Though fragmentary, this archeoview is pregnant with secrets yet to be discovered and is thrilling in its potential. Secrecy is power even if it is just a little something kept from view, buried, so to speak, in the matrix of everyday life,” Sanborn divulges in this context. “For the past 30 years, my task as  an artist has been to release this hidden information at a rate commensurate with its importance, and at the time of my choosing so as to prolong the experience of discovery.”

an artist has been to release this hidden information at a rate commensurate with its importance, and at the time of my choosing so as to prolong the experience of discovery.”

If anyone does manage to solve Kryptos‘ last cipher, that won’t end the hunt for the ultimate truth about the sculpture. “There may be more to the puzzle than what you see,” Scheidt says. “Just because you broke it doesn’t mean you have the answer.”

“In part of the code that’s been deciphered, I refer to an act that took place when I was at the agency and a location that’s on the ground of the agency,” Sanborn told Wired in 2005. He may be referring to something he buried on the CIA grounds, though he won’t say for sure. The decrypted text gives latitude and longitude coordinates (38 57 6.5 N, 77 8 44 W), which Sanborn has said refer to “locations of the agency.”

All of this leads one to ask: Is there a solution? Sanborn insists there is—but he would be just as happy if no one ever discovered it. “In some ways, I’d rather die knowing it wasn’t cracked,” he says. “Once an artwork loses its mystery, it’s lost a lot.”

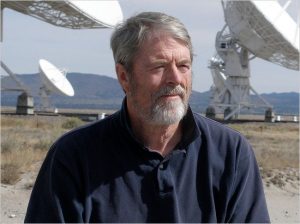

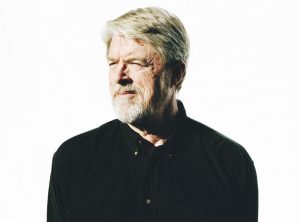

A Word About Jim Sanborn

Born November 14, 1945 in Washington D. C., James Sanborn would spend his childhood in Alexandria, Virginia, attending JEB Stuart High School in Fairfax. His career began to take shape as he studied archaeology at Oxford University and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree with a double major in art history and sociology from Randolph-Macon College in 1968. In 1971 he earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in Sculpture from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He was a teacher at Montgomery College in Rockville and at Glen Echo Park.

Born November 14, 1945 in Washington D. C., James Sanborn would spend his childhood in Alexandria, Virginia, attending JEB Stuart High School in Fairfax. His career began to take shape as he studied archaeology at Oxford University and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree with a double major in art history and sociology from Randolph-Macon College in 1968. In 1971 he earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in Sculpture from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He was a teacher at Montgomery College in Rockville and at Glen Echo Park.

Sanborn is famous for his work with American stone in abstract art that  demonstrates the hidden forces of nature and a sense of mystery.

demonstrates the hidden forces of nature and a sense of mystery.

“Prior to the Kryptos commission my work documented hidden or invisible natural forces, Earth’s magnetic field etc.,” Sanborn said in a 2012 e-interview he gave to Yin Ho of rhizome.org. “For the Kryptos piece and for the 20 years since, the hidden forces/content in text and language have taken over.  For most of my life both of my parents worked at the Library of Congress, my father as the Director of Exhibitions and my mother as a photo researcher. This privileged access to the historic record was tremendously enabling. The texts I chose for my public projects were heavily researched at the L.C. and in these works, in particular the international, classical, and Native American texts were used to encourage collaboration

For most of my life both of my parents worked at the Library of Congress, my father as the Director of Exhibitions and my mother as a photo researcher. This privileged access to the historic record was tremendously enabling. The texts I chose for my public projects were heavily researched at the L.C. and in these works, in particular the international, classical, and Native American texts were used to encourage collaboration  among cultures to fully decipher. Like Kryptos, the other public works are designed to exude their information slowly.”

among cultures to fully decipher. Like Kryptos, the other public works are designed to exude their information slowly.”

Sanborn has installed works all over the world, including All the Ships Sailed in Circles at the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts in Taiwan, The Cryllic Projector at the University of North Carolina, Coastline at the National Oceanic & Atmospheric  Administration in Maryland, Antipodes at Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D. C., Wealth of Nations at Cleveland State University, Binary Systems at the Central Computing Facility Internal Revenue Service in Martinsburg, West Virginia, an incised copper and granite piece titled Comma which lights up the plaza in front of the new library at the University of Houston (2004) and bronze projection cylinders with waterjet cut text named Radiance at the Department of Energy, Coast and Environment at Lousiana State University (LSU) (2008).

Administration in Maryland, Antipodes at Hirshhorn Museum in Washington D. C., Wealth of Nations at Cleveland State University, Binary Systems at the Central Computing Facility Internal Revenue Service in Martinsburg, West Virginia, an incised copper and granite piece titled Comma which lights up the plaza in front of the new library at the University of Houston (2004) and bronze projection cylinders with waterjet cut text named Radiance at the Department of Energy, Coast and Environment at Lousiana State University (LSU) (2008).

Sanborn also has pieces at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Numark Gallery and the federal courthouse in Beltsville, Maryland. Other works  by Sanborn have been exhibited in the High Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Phillips Collection. Sanborn is currently developing a new body of museum and gallery works about the global trade in looted antiquities.

by Sanborn have been exhibited in the High Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Phillips Collection. Sanborn is currently developing a new body of museum and gallery works about the global trade in looted antiquities.

Selected Collection

Even if the CIA is frustrated (if not more than a little embarrassed) by their long-standing inability to decipher the fourth encryption, they nevertheless join a list of more than 125 prestigious institutions who are proud to include Sanborn’s work among their collections, including:

- The Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC

- The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- National Museum of American Art, Washington, DC

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA

- Kaohsiung Museum Of Fine Arts, Republic of China.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring, MD

- The Central Intelligence Agency, Langly, VA (GSA)

- The National Endowment For The Arts, Washington, DC

- Kawasaki International Peace Park, Kawasaki, Japan

- Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, FL

- Southeast Museum of Photography, Daytona Beach, FL

- Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, NV

- Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA

- US Embassy, Dublin, Ireland

- Progressive Insurance, Cleveland, OH

- University Of Houston, Houston, TX

- University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA

- University of California SF, San Francisco, CA

A Word about the Maskoki Migration Legend Sanborn Used in the Eastern Drum

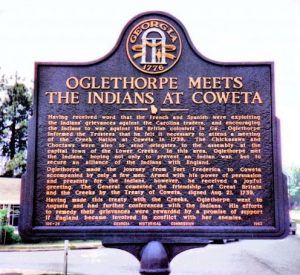

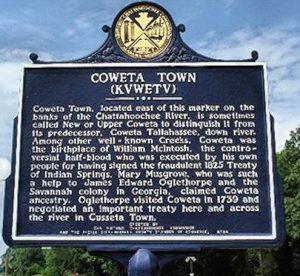

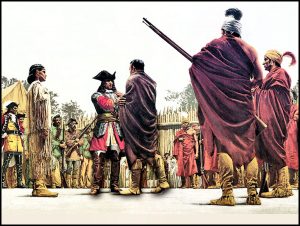

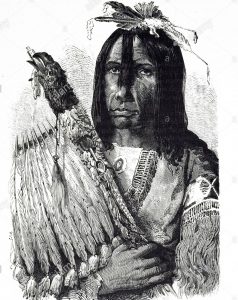

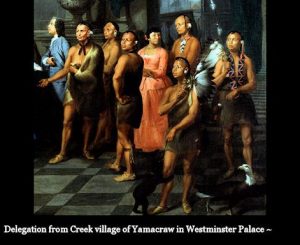

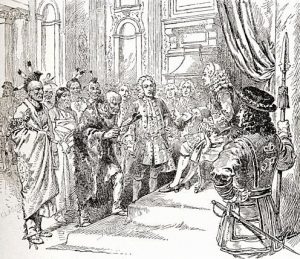

As previously mentioned, the eastern projection cylinder of Caloosahatchee Manuscripts reproduces text from the Maskoki Kasi’hta migration legend told by Tchikilli (whose name is also sometimes spelled Chikilli or Chikili). The “emperor” or “high king” of the Upper and Lower Creeks, Tschikilli attended a council of Indian leaders that was held in Savannah, Georgia on June 7, 1735 in the presence of the Ggovernor of the Carolinas and the founder of Georgia, General James Oglethorpe, and the Secretary of the Province of Georgia, Thomas Christie. According to Richard Thorton (who is considered one of the nation’s leading experts on Southeastern Indians),

As previously mentioned, the eastern projection cylinder of Caloosahatchee Manuscripts reproduces text from the Maskoki Kasi’hta migration legend told by Tchikilli (whose name is also sometimes spelled Chikilli or Chikili). The “emperor” or “high king” of the Upper and Lower Creeks, Tschikilli attended a council of Indian leaders that was held in Savannah, Georgia on June 7, 1735 in the presence of the Ggovernor of the Carolinas and the founder of Georgia, General James Oglethorpe, and the Secretary of the Province of Georgia, Thomas Christie. According to Richard Thorton (who is considered one of the nation’s leading experts on Southeastern Indians),  Christie recorded the legend that Tchikilli related to Oglethorpe during this conference.

Christie recorded the legend that Tchikilli related to Oglethorpe during this conference.

“It seems established that a contemporary English translation [of the Kash’hta migration legend], written in red and black letters on a buffalo hide,  was handed over to the British authorities, sent to England, and in the same year translated into German,” writes Smithsonian Institute ethnologist Albert Samuel Gatschet in his review titled A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians (Vol. 1, Philadelphia) in The Academy (Vol. 27, Jan. 17, 1885). The German translation was codified in von Rock’s Diarium von seiner Reise nach Georgien im Jahr (1735).

was handed over to the British authorities, sent to England, and in the same year translated into German,” writes Smithsonian Institute ethnologist Albert Samuel Gatschet in his review titled A Migration Legend of the Creek Indians (Vol. 1, Philadelphia) in The Academy (Vol. 27, Jan. 17, 1885). The German translation was codified in von Rock’s Diarium von seiner Reise nach Georgien im Jahr (1735).

Gatschet actually got this a bit wrong. Tchikilli actually brought  the buffalo calfskin velum with him and presented it to Ogelthorpe as a gift. Tchikilli then read the velum aloud. As he did, Mary Musgrove translated his words into English. As she did, Thomas Christie wrote them down. After this presentation, Oglethorpe, Tchikilli and the other Creek leaders discussed other issues that would formalize their relationship with the new colony.

the buffalo calfskin velum with him and presented it to Ogelthorpe as a gift. Tchikilli then read the velum aloud. As he did, Mary Musgrove translated his words into English. As she did, Thomas Christie wrote them down. After this presentation, Oglethorpe, Tchikilli and the other Creek leaders discussed other issues that would formalize their relationship with the new colony.

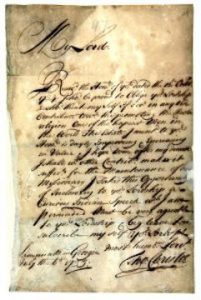

Recognizing that the velum and Christie’s translation were  proof positive that at least one Native American people were literate, Oglethorpe directed Christie to send the buffalo skin and his English translation to England on the next available ship. Christie also sent along a cover letter introducing them both. It is possible that Oglethorpe himself may have accompanied the velum, translation and Christie’s letter on that ship.

proof positive that at least one Native American people were literate, Oglethorpe directed Christie to send the buffalo skin and his English translation to England on the next available ship. Christie also sent along a cover letter introducing them both. It is possible that Oglethorpe himself may have accompanied the velum, translation and Christie’s letter on that ship.

The arrival of the Creek Migration Legend and its English translation created an immediate stir in London. Excerpts of the document were published in several London newspapers. The most  extensive coverage was in the American Gazetteer, which wrote: “This speech was curiously written in red and black characters on the skin of a young buffalo and translated into English as soon as delivered in the Indian language. . . . The said skin was set in a frame and hung up in the Georgia Office in Westminster.”

extensive coverage was in the American Gazetteer, which wrote: “This speech was curiously written in red and black characters on the skin of a young buffalo and translated into English as soon as delivered in the Indian language. . . . The said skin was set in a frame and hung up in the Georgia Office in Westminster.”

The framed buffalo skin went missing around 1762 and has never been seen again. So the legend was translated back into English from von Rock’s German version by Judge G.W. Stidham.

The framed buffalo skin went missing around 1762 and has never been seen again. So the legend was translated back into English from von Rock’s German version by Judge G.W. Stidham.

It is not known how Jim Sanborn came across the re-translated English text during the research he conducted in conjunction with Caloosahatchee Manuscripts, or why he chose the Kasi’ hta migration  legend excerpt that he used for the eastern projection cylinder. But the text he incised into the easternmost projection cylinder of his light sculpture translates as follows:

legend excerpt that he used for the eastern projection cylinder. But the text he incised into the easternmost projection cylinder of his light sculpture translates as follows:

“After four years they left the Coosaws, and came to a river which they called Nowphawpe, now Callasi-Hutchee. There they tarried two years; and as they had no corn, they lived on roots and fishes, and made bows, pointing the arrows with beaver-teeth and flint-stones, and for knives they used split canes. They left this place and came to a creek called Wattoola-Hawka-Hutchee, Whooping Creek, so called from the whooping of cranes, a great many being there; they slept there one night.  They next came to a river in which there was a waterfall; this they named the Owatunka River. The next day they reached another river, which they called the Aphoose Pheeskaw. The following day they crossed it and came to a high mountain, where people who, they believed, were the same who made the white path. They, therefore, made white arrows and shot them, to see if they were good people. But the people took their white arrows, painted them red, and shot them back. When they showed them to their chief, he said that it was not a good sign; if the arrows returned had been white, they could have gone there and brought food for their children, but as they were red, they must not go. Nevertheless, some of them went to see what sort of people they were;

They next came to a river in which there was a waterfall; this they named the Owatunka River. The next day they reached another river, which they called the Aphoose Pheeskaw. The following day they crossed it and came to a high mountain, where people who, they believed, were the same who made the white path. They, therefore, made white arrows and shot them, to see if they were good people. But the people took their white arrows, painted them red, and shot them back. When they showed them to their chief, he said that it was not a good sign; if the arrows returned had been white, they could have gone there and brought food for their children, but as they were red, they must not go. Nevertheless, some of them went to see what sort of people they were;  and found their houses deserted. They also found a trail that led to the river; and, as they could not see the trail on the opposite bank, they believed that the people had gone into the river, and would not again come forth. At that place is a mountain called Motorell, which makes a noise like beating on a drum.”

and found their houses deserted. They also found a trail that led to the river; and, as they could not see the trail on the opposite bank, they believed that the people had gone into the river, and would not again come forth. At that place is a mountain called Motorell, which makes a noise like beating on a drum.”

At first blush, it may seem that the reference in the preceding  text to the Callasi-Hutchee is to the Caloosahatchee River. It is not. The Callisi-Hutchee refers to the Chattahoochee River, which contains a waterfall that divides the slow-moving waters downstream from the clear, swift current above. It appears that the Maskoki (also spelled Muscogee) followed the river to its headwaters in the mountains near present-day Columbus, Georgia. Large mounds and other earthworks on both sides of the river in this

text to the Callasi-Hutchee is to the Caloosahatchee River. It is not. The Callisi-Hutchee refers to the Chattahoochee River, which contains a waterfall that divides the slow-moving waters downstream from the clear, swift current above. It appears that the Maskoki (also spelled Muscogee) followed the river to its headwaters in the mountains near present-day Columbus, Georgia. Large mounds and other earthworks on both sides of the river in this  vicinity attest to the importance of the site in ancient days.

vicinity attest to the importance of the site in ancient days.

Sanborn could, and perhaps should, have referred to the east drum as Maskoki Manuscripts, but he opted to name it and the entire sculpture “Caloosahatchee” Manuscripts instead. That’s because he was seeking to make a connection between the Maskoki/Muscogee and Seminoles to their predecessors, the Calusa Indians, who inhabited what is  now Fort Myers from 500 to 1700 A.D. The last of the Calusa died off roughly 200 years after the arrival of Ponce de Leon and the Spanish Conquistadors in 1513. The light sculpture today sits on the site of a Calusa settlement, and Sanborn would have preferred to reference that connection in the eastern projection cylinder but the Calusa left no written record. But the Creeks or Seminoles did “and the Seminole tribe is important to Florida.” So the name “Caloosahatchee” Manuscripts is an amalgamation that pays homage to both the importance of the site to the Calusa Indians and the importance of the Seminoles to both Fort Myers and the State of Florida as a whole.

now Fort Myers from 500 to 1700 A.D. The last of the Calusa died off roughly 200 years after the arrival of Ponce de Leon and the Spanish Conquistadors in 1513. The light sculpture today sits on the site of a Calusa settlement, and Sanborn would have preferred to reference that connection in the eastern projection cylinder but the Calusa left no written record. But the Creeks or Seminoles did “and the Seminole tribe is important to Florida.” So the name “Caloosahatchee” Manuscripts is an amalgamation that pays homage to both the importance of the site to the Calusa Indians and the importance of the Seminoles to both Fort Myers and the State of Florida as a whole.

Full Migration Legend of the Creek People Found in 2015

Wheras the buffalo skin velum was framed and hung on a wall, Christie’s English translation was stored away in a wooden crate (with some other valuable documents) someplace in Lambeth Palace (which was the official residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury) and ultimately forgotten. After the buffalo skin disappeared, a search was made for Christie’s translation, but that too was never found. “The

Wheras the buffalo skin velum was framed and hung on a wall, Christie’s English translation was stored away in a wooden crate (with some other valuable documents) someplace in Lambeth Palace (which was the official residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury) and ultimately forgotten. After the buffalo skin disappeared, a search was made for Christie’s translation, but that too was never found. “The  chances of rediscovering the original English translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People are therefore almost as slim as recovering the lost books of Livy’s History,” lamented Albert Samuel Gatschet.

chances of rediscovering the original English translation of the Migration Legend of the Creek People are therefore almost as slim as recovering the lost books of Livy’s History,” lamented Albert Samuel Gatschet.

And for 280 years, Gatschet appeared to be right. But then on April 29, 2015, Dr. Grahamme Davies, a famous Welch poet  who now serves as Assistant Private Secretary for HRH Prince Charles, happened upon the crate and the lost translation. When the original document and the German translation were compared, scholars were dismayed to find that the German text was neither all that accurate or complete. “Although the text of the two documents follow the same general pattern, there were changes made in some of the passages that completely

who now serves as Assistant Private Secretary for HRH Prince Charles, happened upon the crate and the lost translation. When the original document and the German translation were compared, scholars were dismayed to find that the German text was neither all that accurate or complete. “Although the text of the two documents follow the same general pattern, there were changes made in some of the passages that completely  changed the meanings of certain phrases and sentences,” notes Access Genealogy. Some of the sentences were actually presented in reverse order.

changed the meanings of certain phrases and sentences,” notes Access Genealogy. Some of the sentences were actually presented in reverse order.

It now emerges that there are three separate migration legends in all.

The first is the Itsate Creek Migration Legend. This one indicates that descendants of the Itza Maya came to North America from the sea, landing in Florida (“a land of marshes”). They then migrated northward to either the Okefenokee Swamp or Lake Tama in Middle Georgia before  settling in the Georgian mountains, where they built powerful towns that controlled all trade routes in the Appalachian Mountains.

settling in the Georgian mountains, where they built powerful towns that controlled all trade routes in the Appalachian Mountains.

The second is the Apalache Creek Migration Legend. This legend postulates that the Creek sailed the Gulf Stream north, coming ashore in present-day Savannah. They named the settlement they built there Apalache, which is a Peruvian word that means “offspring from the sea.” Eventually, these Creek migrated to Lake Tama before moving northward, where they became vassals of the Itsate until they overthrew their masters and created a powerful kingdom that spanned from southwestern Virginia to the Florida Panhandle (and which archeologists  identify as the Lamar Culture).

identify as the Lamar Culture).

The third migration legend is the one that contains the excerpt which Sanborn incised into the eastern drum of Caloosahatchee Manuscripts. It encompasses the majority of provinces to which the Creek migrated, and begins west of the Mississippi on the slopes of a volcano in northwestern Mexico and ends in eastern Alabama and western Georgia.

A Word about Tschkilli’s Maskoki

According to Richard Thornton, this third “Muskogee-Creek Migration Legend … is actually a saga about the Taskete (Tesquita), a Tolteca tribe which migrated to northwest Georgia and then took on the name of their landlords, the Kawshe (Kusa). In their migration legend …, they were called the Kawshete, which means ‘Kusa People.’ Whereas the Taskete/Tuskegee continued to speak a Mesoamerican language similar to Itza Maya and Huastec, the Cusseta in Georgia eventually adopted the language of Coweta, which is now called Muskogee.”

According to Richard Thornton, this third “Muskogee-Creek Migration Legend … is actually a saga about the Taskete (Tesquita), a Tolteca tribe which migrated to northwest Georgia and then took on the name of their landlords, the Kawshe (Kusa). In their migration legend …, they were called the Kawshete, which means ‘Kusa People.’ Whereas the Taskete/Tuskegee continued to speak a Mesoamerican language similar to Itza Maya and Huastec, the Cusseta in Georgia eventually adopted the language of Coweta, which is now called Muskogee.”

Originally, the Taskete (Kaushete) lived in caves on the slopes of the Orizaba  Volcano in Mexico’s Southwestern Vera Cruz State. “After learning how to grow crops, they migrated up and down the Yama (Jamapo) River, which even today is often called the Bloody River,” Thornton expounds. “After being persecuted by more advanced people, they migrated along the edge of the Gulf of Mexico on the Great White Path until they reached the Mississippi River Basin. There they dwelled for several generations before migrating due east. They eventually settled in the land of the Kawshe, now typically called the Kusa. Their town was visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition and called Tasqui. It most likely was the site of a large Proto-Creek town and Cherokee village on the edge of Fontana Lake, now called Tuskeegee.”

Volcano in Mexico’s Southwestern Vera Cruz State. “After learning how to grow crops, they migrated up and down the Yama (Jamapo) River, which even today is often called the Bloody River,” Thornton expounds. “After being persecuted by more advanced people, they migrated along the edge of the Gulf of Mexico on the Great White Path until they reached the Mississippi River Basin. There they dwelled for several generations before migrating due east. They eventually settled in the land of the Kawshe, now typically called the Kusa. Their town was visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition and called Tasqui. It most likely was the site of a large Proto-Creek town and Cherokee village on the edge of Fontana Lake, now called Tuskeegee.”

A  terrible drought struck the mountains beginning around 1585. At that time, a band of Taskete fled upstream until they reached the terminus of the Great White Path at Chiaha.

terrible drought struck the mountains beginning around 1585. At that time, a band of Taskete fled upstream until they reached the terminus of the Great White Path at Chiaha.

“Great White Path is the English translation of the Itza Maya name for a major road,” notes Thornton. The adjective white signifies that no warfare was allowed along this route. Now known as US Highway 129, this  route connects the Great Smoky Mountains with the Gulf Coast of Florida and passes through most of the indigenous town sites in western North Carolina, Georgia and North Florida.

route connects the Great Smoky Mountains with the Gulf Coast of Florida and passes through most of the indigenous town sites in western North Carolina, Georgia and North Florida.

“The real site of Chiaha is quite visible in Fontana Lake, just downstream of where, as stated by De Soto’s chroniclers, three rivers meet . . . the Little Tennessee, Nantahala and Tuckasegee. From Chiaha, this band traveled southward on the Great White Path to a large town on the side of a mountain, occupied  by people with flattened foreheads. This was probably the Track Rock Terrace Complex. The band ransacked the town then fled southward until they reached the lower Georgia Mountains and the Province of Apalache. Here they were given sanctuary and assigned to live across the river from the town of Coweta. From then on, the Coweta and Cusseta paired their towns, wherever they established colonies.”

by people with flattened foreheads. This was probably the Track Rock Terrace Complex. The band ransacked the town then fled southward until they reached the lower Georgia Mountains and the Province of Apalache. Here they were given sanctuary and assigned to live across the river from the town of Coweta. From then on, the Coweta and Cusseta paired their towns, wherever they established colonies.”

How the Maskoki/Muscogee Came to Migrate into Florida

The narrative here resumes with the Creek War of 1813-1814, which began as a civil war within the Muscogee Nation but quickly became enmeshed in the War of 1812. A faction of the Muscogee known as the Red Sticks joined forces with the British. Led by Shawnee leader Tecumseh, William Red Eagle Weatherford, Peter McQueen and Menawa, the Red Sticks prosecuted a number of bloody campaigns, including the Battle of Burnt Corn, the Fort Mims Massacre and the Kimbell-James Massacre.

The United States duly responded. Under the command of General Andrew Jackson, the Tennessee militia, aided by the 39th U. S. Infantry Regiment and Cherokee and Lower Creek warriors, crushed the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River, leading to their surrender and a peace treaty (the Treaty of Fort Jackson) that required the Muscogee Nation to cede 20 million acres of land to the United States (much of which was located in present day Alabama).

Many Muscogee refused to surrender and escaped instead to Florida. There, they allied themselves with other remnant tribes, particularly the Seminole. So many Red Stick refugees came to Florida and merged with the Seminole tribe that they tripled the Seminole population which, predictably, took on many Muscogee characteristics.

Because the reconstituted Seminoles welcomed fugitive slaves and conducted raids against settlers who attempted to relocate onto their lands, the United States declared war and invaded Florida in 1818. With General Andrew Jackson once again in command, federal forces destroyed Seminole towns and captured Pensacola. Not prepared to engage in a lengthy and expensive war across the Atlantic Ocean, Spain entered into a treaty (the Adams-Onis Treaty) in 1819 under which it ceded Florida to the United States. Left with little other choice, the remaining Seminoles/Muscogee agreed to move into and remain in the central and southern part of the peninsula, where they were pretty much left alone for a time.

Andrew Jackson then ran for and was elected president. He quickly introduced an Indian Removal Bill into Congress, which narrowly passed the legislation. Following the Bill’s enactment, most of the Muscogee still living in Georgia, Tennessee and Alabama were removed (sometimes forcibly) to reservations in Arkansas and Oklahoma in 1834. Today, the path they took is descriptively known as the Trail of Tears.

While the Muscogees and Seminoles living in Florida had largely escaped notice and the long arm of the Indian Removal Bill at that time, two years later the United States initiated a new war with the objective of deporting the remaining Native Americans living in Florida to make way for wealthy plantation owners who had in mind to drain the Everglades and install mammoth sugar cane and rice plantations worked by slave labor.

The Second Seminole War raged for the next seven years. By the time it finally ended in February of 1842, 3,930 Indians had been deported to Arkansas and Oklahoma, with hundreds more dying in battle or from starvation and disease. Less than 600 Native Americans remained in all of Florida. By treaty, they were confined in a large swath of land south of the Peach River and west of the midline through Lake Okeechobee.

But even this number was too many for the settlers who continued to flood into Florida in the years following the cessation of hostilities. After trying unsuccessfully to persuade Chief Billy Bowlegs and his people to voluntarily leave the lands for which they had spilled copious amounts of blood, federal troops instigated a third war, which the United States waged from 1855 through May of 1858. It ended with the surrender and deportation of Chief Bowlegs and 123 of this fellow tribesmen and women to Oklahoma (where he and many of their number died a year later in a small pox outbreak). Although another hundred or so Indians refused to leave, the federal government did not pursue them into their hideouts deep inside the Everglades.

Today the Miccosukee are the last remaining vestiges of the Creek and Muscogee living in the state.

July 5, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Thanks for the Caloosahatchee Manuscript info. I was able to figure out the Edison one but was stumped about the cylinder on the NE side.

I have located a translation of the Creek Text, which was originally transcribed from a verbal account in 1735, written onto buffalo skin in red and black characters in the Maskoki language.

The original was transported to England and hung in the Georgia office in Westminster, London until 1762 when it was discovered to be lost.

Fortunately, the text had been preserved in a Protestant German translation describing the treatment of American colonies, published in 1741.

In 1870, the legend was translated from German into English and mentioned in the New York Historical Magazine.

Finally, the Kasi’ta Migration Legend was published, in both Maskoki and English, in The Transactions of The Academy of Science Of St. Louis, Vol. V, 1986-88, and begins “NAKI TCHIKILLI ISTI MASKOKI”.

I’m a big fan of cryptography and Jim Sanborn’s work.

I would think most interested in history would promote investigating history for one’s self. This is one way to discover the joy of history. Sanborn is a genius, pointing people to the path of discovery is a moral culture.

Please remove my comment of July 12,2012 at 12:25 am, thankfully the article’s content was changed and more info added. My above comments address an issue you have resolved.

LUX is a public work of art, there is a translation. Thank you for adding further information, it shows the value of the individual artist to the Public Art Committee of Ft Myers and culture at large as I am a driving force here in pushing for humanistic emphasis in our Lee visual cultural public art issues. Of course their is much more to this incredible work, the meaning is washing over us in the light it projects and in their daytime solemn witness. It seems strange I am the only curious artist in town asking about the reality of LUX. It seems our Lee visual culture forgot to inform the artists and public to be on the alert for the genius of modernism. I wish you would record my contribution to our culture for our PAC. You have come a long way from your original statement that LUX was a story of not much interest. I have asked institutions and art officers here for the last few years about this translation and no one will respond to me. This is now part of the story of LUX as I am a professional ideological modernist visual composer / artist and I have been asking for our humanistic cultural record reasons. BFA