Caloosahatchee Water Wall draws attention to river’s history and complex water quality issues

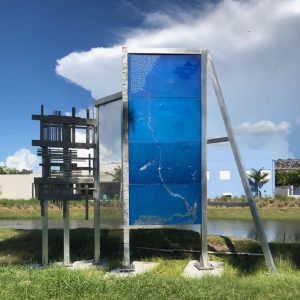

As the relentless rays of the sun bathed them, a four-man crew installed the steel beams and aluminum panels of Michael Singer’s Caloosahatchee Water Wall on the western perimeter of the Alliance for the Arts’ 10-acre campus along McGregor Boulevard. Additional landscaping, ground work and pavers will be installed over the following 4 weeks. But months in the planning, the project has finally come to fruition, and it’s been well worth the wait.

As the relentless rays of the sun bathed them, a four-man crew installed the steel beams and aluminum panels of Michael Singer’s Caloosahatchee Water Wall on the western perimeter of the Alliance for the Arts’ 10-acre campus along McGregor Boulevard. Additional landscaping, ground work and pavers will be installed over the following 4 weeks. But months in the planning, the project has finally come to fruition, and it’s been well worth the wait.

The piece is multi-dimensional. The blue panels depict the Caloosahatchee  River. But it functions as a filter as well, sweeping up water from the adjoining newly-reshaped storm water retention pond and allowing it to trickle back down, dripping, reeling and splashing onto plants and soil at the base in one last shining and slow-moving wash before it makes it way out to the Caloosahatchee, where it joins the river’s other slow-moving waters en route to the estuaries and Gulf of Mexico.

River. But it functions as a filter as well, sweeping up water from the adjoining newly-reshaped storm water retention pond and allowing it to trickle back down, dripping, reeling and splashing onto plants and soil at the base in one last shining and slow-moving wash before it makes it way out to the Caloosahatchee, where it joins the river’s other slow-moving waters en route to the estuaries and Gulf of Mexico.

Since the day Brevet Major Ridgely of the 4th U.S. Artillery sailed up the Caloosahatchee River and landed on the site of the ruins of long-abandoned Fort Harvie with orders to build a new and expanded military outpost, Fort Myers has enjoyed a special relationship with its  river. Fort Myers’ first settlers, Manuel A. Gonzalez and his son, came by boat. Tarpon fishing and the river’s scenic beauty were what attracted early developers like Paul O’Neill, Peter Tonnelier, and Ambrose and Tootie McGregor. These factors were also important to Thomas Edison, who was inspired by the river to create botanical gardens and a laboratory on its southern bank.

river. Fort Myers’ first settlers, Manuel A. Gonzalez and his son, came by boat. Tarpon fishing and the river’s scenic beauty were what attracted early developers like Paul O’Neill, Peter Tonnelier, and Ambrose and Tootie McGregor. These factors were also important to Thomas Edison, who was inspired by the river to create botanical gardens and a laboratory on its southern bank.

Although the town marketed the Caloosahatchee as “the prettiest river in the  entire state” as far back as 1907, Fort Myers’ relationship with the river has been characterized by a pervasive lack of responsible stewardship over much of its 150-year history.

entire state” as far back as 1907, Fort Myers’ relationship with the river has been characterized by a pervasive lack of responsible stewardship over much of its 150-year history.

Envisioning Fort Myers as a “gateway city” to vast development in the center of the state, most residents were “all in” when the Florida Legislature sold millions of acres of land to Hamilton Disston in furtherance of its desire to drain the Everglades in order to establish lush sugar cane and cotton plantations in the rich black muck south of Lake Okeechobeee. As a consequence, little thought was given to preserving  the river’s pristine condition and water quality as Disston and his successors dredged canals connecting the Caloosahatchee first to Lake Okeechobee and later to a series of canals designed to establish a cross-state waterway to Kissimmee to the north and Fort Lauderdale to the southeast.

the river’s pristine condition and water quality as Disston and his successors dredged canals connecting the Caloosahatchee first to Lake Okeechobee and later to a series of canals designed to establish a cross-state waterway to Kissimmee to the north and Fort Lauderdale to the southeast.

Then the 1928 hurricane struck, drowning more than 3,500 people as the resulting winds and torrential rainfall caused Lake Okeechobee to breech its southern banks. In a classic overreaction, the federal government diked the lake, laying the predicate for our chronic water woes,  characterized by the Army Corps of Engineers restricting water flow during dry season and droughts and dumping massive amounts of nutrient-rich, herbicide/pesticide laden water into the river during rainy season.

characterized by the Army Corps of Engineers restricting water flow during dry season and droughts and dumping massive amounts of nutrient-rich, herbicide/pesticide laden water into the river during rainy season.

By 2006, the river was not just sick, it was dying. In fact, American Rivers designated the Caloosahatchee as the 7th  most endangered river in the nation. And to this day, the river, its estuaries and the gulf waters at the mouth of the river are plagued by recurring cyanobacteria blooms, blue-green macroalgae outbreaks and red tide, with residents and visitors inconvenienced by swimming bans and shellfish advisories and endangered with respiratory conditions and elevated levels of childhood cancers, particularly leukemia.

most endangered river in the nation. And to this day, the river, its estuaries and the gulf waters at the mouth of the river are plagued by recurring cyanobacteria blooms, blue-green macroalgae outbreaks and red tide, with residents and visitors inconvenienced by swimming bans and shellfish advisories and endangered with respiratory conditions and elevated levels of childhood cancers, particularly leukemia.

Although a large portion of these problems are attributed to harmfully large releases of polluted water from Lake Okeechobee and surrounding farms and cattle ranches, the Conservancy of Southwest Florida’s 2011 Estuaries Report Card also noted that a large proportion (roughly 60%) of the river’s nutrient pollution comes from its stormwater runoff watershed.

Hence, one of the functions of the new Caloosahatchee Water Wall is filtering the runoff that collects in the stormwater detention pond sandwiched in between McGregor Boulevard and the Alliance for the Arts. In this, the Water Wall echoes the function and purpose of the City’s 1.8 acre river basin, which collects and filters water from the surrounding 15-acre downtown area. Like the Water Wall, the basin contains percolating fountains that aerate the water while plants absorb fertilizers and other nutrients that don’t belong in the Caloosahatchee.

The Water Wall is the anchor of the Alliance’s overarching ArtsPark, which includes new crosswalks, sidewalk, pathways, lighting, landscaping that reflects Southwest Florida ecosystems and space for dozens of pieces of outdoor artworks. But it is the hope of the Alliance that the Caloosahatchee Water Wall will draw attention to the river’s history and the City’s need to protect it from harm now and in the future.

“It is truly an honor being selected by the Alliance for the Arts as the artist to create a public sculpture for this inspiring Fort Myers based organization,” says artist Michael Singer. “My hope is the Caloosahatchee Water Wall sculpture becomes a distinguishing work of art for the Alliance while also providing the larger community with an understanding of interconnections between very special natural water systems of the Caloosahatchee River as well as our responsibility to take on damaging environmental human impacts. My hope is that this Water Wall sculpture motivates positive actions that will address complex water quality issues in the region.”

But message and theme aside, the Caloosahatchee Water Wall is first and foremost a work of public art. In this regard, seminal Fort Myers Public Art Committee member and Alliance supporter Ava Roeder heaped high praise on the Water Wall from an artistic standpoint. “This is probably the best public art we have in the City. It is an overall beautiful work of art and there is visual interest from every angle.”

Michael Singer has received numerous awards, including fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. His works are part of public collections in the United States and abroad, including the Australian National Gallery, Canberra; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark; the Guggenheim Museum, New York; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“It has been a pleasure watching the Alliance campus transform into a space that draws the community in and encourages creativity,” says Alliance for the Arts executive director Lydia Black. “We are enormously grateful artist to artist Michael Singer, the campus enrichment team, the Alliance staff and Board and the countless community partners who have made this project possible.”

Campus improvements are supported in part by John E. & Aliese Price Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Frizzell Family Foundation, Deborah Meisenberg Family Trust, L.A.T. Foundation, Rotary Club of Fort Myers South, a special gift in memory of Lucille Remler, Huffer Foundation, Keep Lee County Beautiful Foundation, LCEC, The Claiborne and Ned Foulds Foundation and a multitude of Alliance members and patrons.

For more information on the Alliance for the Arts or the Alliance ArtsPark, visit ArtInLee.org/ArtsPark.

June 24, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.