With ‘Hedley,’ playwright August Wilson uses Greek tragedy to illustrate black experience in America

King Hedley II is on stage in the Foulds Theatre at the Alliance for the Arts for just two more shows. It’s the 9th play in playwright August Wilson’s “American Century Cycle,” and undoubtedly his most underestimated and misunderstood works.

King Hedley II is on stage in the Foulds Theatre at the Alliance for the Arts for just two more shows. It’s the 9th play in playwright August Wilson’s “American Century Cycle,” and undoubtedly his most underestimated and misunderstood works.

In fact, Director Sonya McCarter asserts that it’s so different from his other Century Cycle plays that if you didn’t know who the playwright was, you’d never guess it was August Wilson.

That’s actually  a compliment to August Wilson, who said in a post-Hedley interview that he’d grown bored with the Century Cycle format and wanted to use Greek tragedy to underscore the black experience during Regan-era America.

a compliment to August Wilson, who said in a post-Hedley interview that he’d grown bored with the Century Cycle format and wanted to use Greek tragedy to underscore the black experience during Regan-era America.

Although he wrote Hedley II in 1999, he set the action in 1985 at the high-water mark of the Reagan Administration. It was a time denoted by a breakdown in civility and the scourge of gun violence in the African-American community.  And then, like now, many African-American men labored under the yoke a criminal justice system which, built, honed and entrenched during the Jim Crow era, served to preserve racial order by keeping black people “in their place.” In fact, it seemed like everything in the white world outside “stacks up against you.”

And then, like now, many African-American men labored under the yoke a criminal justice system which, built, honed and entrenched during the Jim Crow era, served to preserve racial order by keeping black people “in their place.” In fact, it seemed like everything in the white world outside “stacks up against you.”

But while the play  certainly functions as an indictment of institutional racism in the criminal justice system and other institutions in American society that produce racially disparate outcomes, the thrust of King Hedley II isn’t on these external factors. Rather, it’s on need of each individual – regardless of color – to assume responsibility for our own manner of thinking and relating to those around us.

certainly functions as an indictment of institutional racism in the criminal justice system and other institutions in American society that produce racially disparate outcomes, the thrust of King Hedley II isn’t on these external factors. Rather, it’s on need of each individual – regardless of color – to assume responsibility for our own manner of thinking and relating to those around us.

Challenging people to recognize, own up to and work to change  their shortcomings isn’t popular now and wasn’t popular then. Presidential candidate received considerable blow-back when he urged in a Father’s Day speech to the NAACP that members of the black community needed to take greater responsibility for improving their own lives. Perhaps anticipating the unpopularity of that message nearly a decade earlier, Wilson resorted to the device of Greek tragedy

their shortcomings isn’t popular now and wasn’t popular then. Presidential candidate received considerable blow-back when he urged in a Father’s Day speech to the NAACP that members of the black community needed to take greater responsibility for improving their own lives. Perhaps anticipating the unpopularity of that message nearly a decade earlier, Wilson resorted to the device of Greek tragedy  in order to give audiences the freedom to consider that theme.

in order to give audiences the freedom to consider that theme.

Greek tragedy centers around a character who is brought to ruin or total destruction by their own actions. That character is typically a good and decent person who suffers from some fatal flaw that leads, ultimately, to their downfall. As formulated by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristotle, the tragic hero always bears at least some responsibility for their own doom.

The  tragic hero’s fatal flaw often manifests in the form of hubris – such as overweening pride or insolence that results in misfortune. In fact, the Greeks believed that cosmic law inevitably exacted retribution as punishment on the part of the gods for such acts of arrogance and temerity. That payback elicits and invokes emotions ranging from pity to fear on the part of the audience, who are thereby induced to evaluate their

tragic hero’s fatal flaw often manifests in the form of hubris – such as overweening pride or insolence that results in misfortune. In fact, the Greeks believed that cosmic law inevitably exacted retribution as punishment on the part of the gods for such acts of arrogance and temerity. That payback elicits and invokes emotions ranging from pity to fear on the part of the audience, who are thereby induced to evaluate their  own lives and make correlative changes to their own behavior, demeanor and lifestyle.

own lives and make correlative changes to their own behavior, demeanor and lifestyle.

Hedley is a desperate mix of anger, rage, resentment and barely-restrained passion. Recently released from prison, he is vainly trying to put down roots in barren soil. Not only can he not find legitimate work (the plight of ex-convicts to this day), he is thwarted in his effort to escape his predicament by the lessons he’s learned and incorporated into his psyche from his parents, their parents and generations tracing  back in time to the plantations – including, in particular, the culture of violence that slaves and their progeny inherited from their white overlords, who used varying degrees of corporeal punishment and the threat of summary execution to stifle their slaves’ innate desire for freedom and self-governance.

back in time to the plantations – including, in particular, the culture of violence that slaves and their progeny inherited from their white overlords, who used varying degrees of corporeal punishment and the threat of summary execution to stifle their slaves’ innate desire for freedom and self-governance.

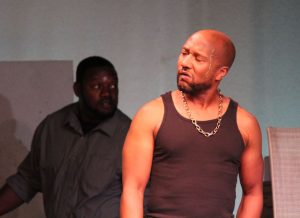

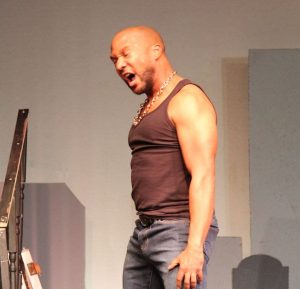

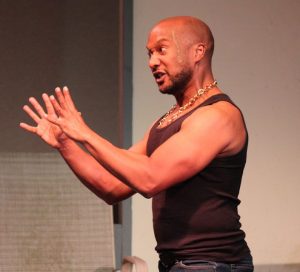

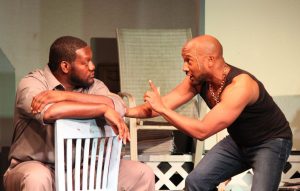

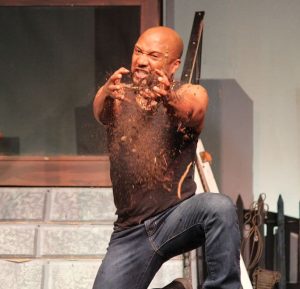

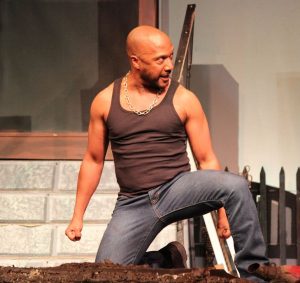

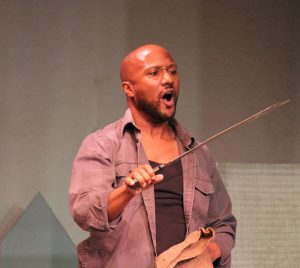

Now if you’re  casting for an actor to play a fatally-flawed tragic hero afflicted with overweening pride, insolence and narcissism, you need a thoughtful, intelligent, self-aware actor with the intentionality to build his character from the inside out. Enter Derek Lively, who’s nitroglycerine on the Foulds Theatre stage.

casting for an actor to play a fatally-flawed tragic hero afflicted with overweening pride, insolence and narcissism, you need a thoughtful, intelligent, self-aware actor with the intentionality to build his character from the inside out. Enter Derek Lively, who’s nitroglycerine on the Foulds Theatre stage.

Lively is no stranger to  August Wilson. He played Canewell for Director Sonya McCarter in Seven Guitars. But Hedley is more akin to Walter Lee Younger in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. Like Walter Lee, Hedley’s rage and anger emanates from fear, anguish and a cognizance of his own mortality. His brushes with death and seven years of incarceration have instilled a burning desire not just for success, but for creating a legacy he can leave behind. But he’s being held back from achieving this lofty goal by his

August Wilson. He played Canewell for Director Sonya McCarter in Seven Guitars. But Hedley is more akin to Walter Lee Younger in Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. Like Walter Lee, Hedley’s rage and anger emanates from fear, anguish and a cognizance of his own mortality. His brushes with death and seven years of incarceration have instilled a burning desire not just for success, but for creating a legacy he can leave behind. But he’s being held back from achieving this lofty goal by his  upbringing, the rampant poverty in the black community, and the oppression imposed by white society and its criminal justice system.

upbringing, the rampant poverty in the black community, and the oppression imposed by white society and its criminal justice system.

He’s also hampered by his own inner sense of right and wrong.

Under McCarter’s direction and in Lively’s capable hands, what emerges from Lively’s portrayal of Hedley is his character’s inflexible  moral compass. The framework from which he operates is not the law imposed by society or religion. There are certain things over which God has no control, he tells his neighbor, Stool Pigeon, at one point during the play. Rather, just as plantation owners showed no mercy to runaway slaves, Hedley refuses to excuse or overlook any transgression. More, he serves as judge, jury and executioner. And it is that trait that makes him a true tragic hero – and ultimately leads to his downfall.

moral compass. The framework from which he operates is not the law imposed by society or religion. There are certain things over which God has no control, he tells his neighbor, Stool Pigeon, at one point during the play. Rather, just as plantation owners showed no mercy to runaway slaves, Hedley refuses to excuse or overlook any transgression. More, he serves as judge, jury and executioner. And it is that trait that makes him a true tragic hero – and ultimately leads to his downfall.

“I told Derek [while they were performing together in Katori Hall’s Mountaintop] that I didn’t like his character,” remarks Director Sonya McCarter.

“I told Derek [while they were performing together in Katori Hall’s Mountaintop] that I didn’t like his character,” remarks Director Sonya McCarter.

“He actually scares me,” she candidly adds.

But in Lively’s portrayal, it becomes evident that Hedley’s menacing, mercurial persona is not merely a reflection of his uncompromising demand for respect and justice. It’s also an overcompensation for deep-seated self-doubt.

Drawing out the nuance, depth and complexity  of characters has become Lively’s trademark, and he exceeds all expectations in his empathic portrayal of King Hedley.

of characters has become Lively’s trademark, and he exceeds all expectations in his empathic portrayal of King Hedley.

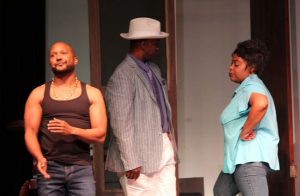

Although she only has two meaningful appearances in the play, so does Cantrella Canady.

“You think you’ve seen Cantrella before?” effuses McCarter. “Oh my gosh, you’ll see her as you’ve never seen her before. She’s a powerhouse.”

Canady is an actor who routinely takes audiences on an emotional journey,  and that’s especially true of her role as Hedley’s girlfriend, Tonya, who discovers early on that she’s pregnant. Tonya is not overjoyed by the news. She was a unwed teen mom whose unwed daughter has herself become a teen mom. And seeing that Hedley is heading down a path that’s likely to land him back in prison for another lengthy bid, Tonya delivers one of August Wilson’s greatest monologues – a cry of desperation from a 35-year old grandmother who cannot stand the very

and that’s especially true of her role as Hedley’s girlfriend, Tonya, who discovers early on that she’s pregnant. Tonya is not overjoyed by the news. She was a unwed teen mom whose unwed daughter has herself become a teen mom. And seeing that Hedley is heading down a path that’s likely to land him back in prison for another lengthy bid, Tonya delivers one of August Wilson’s greatest monologues – a cry of desperation from a 35-year old grandmother who cannot stand the very  thought of bringing another child into a world of limited possibilities and seemingly unbreakable cycle of aggression and retribution.

thought of bringing another child into a world of limited possibilities and seemingly unbreakable cycle of aggression and retribution.

Canady’s delivery is as heartrending as it is breathtaking. Her performance was actually foreshadowed by her character in Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance’s production of Engagement Rules, where she was also called upon to tell her fiance’ that she was going to abort the child he wanted her to have. But there, her motivation  was one of timing. Her character refused to let an unwanted pregnancy (at least on her part) derail her plans to complete law school and enter into a career of social activism.

was one of timing. Her character refused to let an unwanted pregnancy (at least on her part) derail her plans to complete law school and enter into a career of social activism.

In Engagement Rules, the focus was on abortion and the rights, if any, that a putative father has and how he reacts when his mate decides to abort her pregnancy over his objections. The impetus here is qualitatively much different. Tonya would dearly love to have Hedley’s child if the two of them could raise it together.  But what she won’t do is raise that baby alone and condemn the child to the same kind of existence that she finds so objectionable. This makes Tonya a vastly more sympathetic character who’s a tragic figure in her own right.

But what she won’t do is raise that baby alone and condemn the child to the same kind of existence that she finds so objectionable. This makes Tonya a vastly more sympathetic character who’s a tragic figure in her own right.

It’s hard to imagine Canady or Lively exceeding the high standards they’ve set with previous roles, but their performances as  Tonya and Hedley do just that.

Tonya and Hedley do just that.

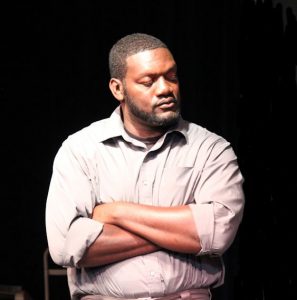

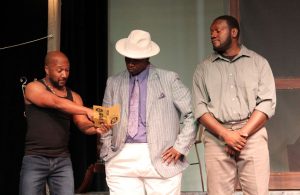

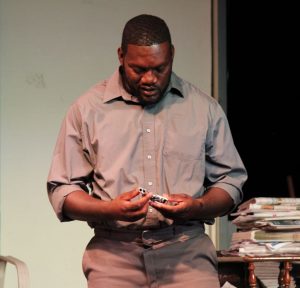

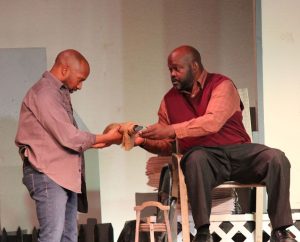

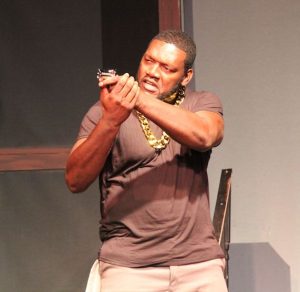

The other performances in King Hedley II are equally powerful and adroit. Tijuanna Clemons is superb in the role of Ruby, Hedley’s mother, an ex-night club performer who nearly killed the musician for whom she sang when he tried to rape her. Lemec Bernard excels as Hedley’s sidekick, Mister, who nearly gets his friend killed in a jewelry store robbery that he concocts in order to get  enough money to buy a bed and some other furnishings after his wife leaves him and cleans out their apartment. And newcomer and recent CHANGE alum Dwayne Donnell does an excellent job with the role of Elmore, Ruby’s old flame and a man with a past that figures prominently in the play’s denouement.

enough money to buy a bed and some other furnishings after his wife leaves him and cleans out their apartment. And newcomer and recent CHANGE alum Dwayne Donnell does an excellent job with the role of Elmore, Ruby’s old flame and a man with a past that figures prominently in the play’s denouement.

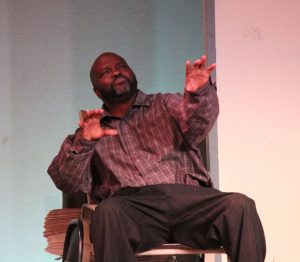

But it is Cicero McCarter who steals many of the scenes in which he appears. McCarter fulfills the function of the orchestra in August Wilson’s Greek tragedy.  He’s a savant, prophet and soothsayer who demonstrates great wisdom and concomitant sadness. It is through the character of Stool Pigeon that Wilson tells his audience that it is time for them to listen to the right people. And it is Stool Pigeon’s role to explore the dichotomy of the pagan beliefs and rituals that the slaves imported from Africa in juxtaposition to the Christian religion that the plantation owners imposed upon them and used

He’s a savant, prophet and soothsayer who demonstrates great wisdom and concomitant sadness. It is through the character of Stool Pigeon that Wilson tells his audience that it is time for them to listen to the right people. And it is Stool Pigeon’s role to explore the dichotomy of the pagan beliefs and rituals that the slaves imported from Africa in juxtaposition to the Christian religion that the plantation owners imposed upon them and used  as a weapon in order to subjugate them. A minister and deeply religious in real life, McCarter had a tough time in coming to terms with Stool Pigeon’s views and discourse, particularly his oft-repeated good-natured observation that “God is a motherfucker.” But he plays the part convincingly, with conviction and belief.

as a weapon in order to subjugate them. A minister and deeply religious in real life, McCarter had a tough time in coming to terms with Stool Pigeon’s views and discourse, particularly his oft-repeated good-natured observation that “God is a motherfucker.” But he plays the part convincingly, with conviction and belief.

Enough good cannot be said of Sonya McCarter’s direction or the chemistry achieved and displayed by the cast of King Hedley II –  a cast, by the way, that had to overcome numerous challenges during the rehearsal process and which is contending now with the ramifications that the COVID-19 outbreak is having on theater groups and performances across the nation, if not the world.

a cast, by the way, that had to overcome numerous challenges during the rehearsal process and which is contending now with the ramifications that the COVID-19 outbreak is having on theater groups and performances across the nation, if not the world.

Kudos to cast, crew and the entire production team on another tour de force August Wilson Century Cycle play.

March 14, 2020.

RELATED POSTS

RELATED POSTS

- Theatre Conspiracy at the Alliance producing August Wilson’s ‘King Hedley II’

- Spotlight on ‘King Hedley’ actor Derek Lively

- For actor, screenwriter, playwright Derek Lively, it’s all a matter of intentionality

- Spotlight on ‘King Hedley’ actor Cantrella Canady

- Just a girl who likes to act, Cantrella Canady takes audiences on emotional journey

Spotlight on ‘King Hedley’ actor Tijuanna Clemons

Spotlight on ‘King Hedley’ actor Tijuanna Clemons- ‘King Hedley’ play dates, times and ticket info

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.